We Will Wait in the Clear Mountain

I am Mountain

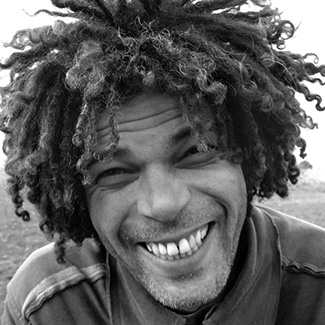

To all appearances it wasn’t your eyes, Alom. Or not just your eyes. And much less could it have been your camera. How can you entrust a dark machine with such delicate mission? Taking pictures has become such an easy and instinctive gesture that anyone could have done it, isn’t it so? After all, the mountain has always been there. Available. Generous. Its door has always been open, like the door of any hut. The river has continued to slide untiringly between the same stones, waiting for the children to come and splash about in their eternal nudity, their joy, and to let themselves fall into the water from the swinging liana. And they have always been there, perhaps with other names the same strong and kind characters, the same bodies, the same hands, hardened by cutting with machete, by using the hoe, by sowing, milking, by driving down the river the rough perfection of the canoes. And our beautiful women have been there always. The mothers surrounded by their many children. That is to say, our mothers, the mothers of Cubans.

But it is a lie that anyone could have made these photos. Taking pictures is not winking, although the mechanism of both operations is almost identical. It does not even have much to do with lens, shutters and diaphragms. Or with the ability or the craft of the photographer, or the elegant tricks of the art. I am tempted to say that photography does not even have to do with the eyes. Photography only has to do with the light. With the quality of the light. Not with the sunlight, the lamp light, but with a certain light that emerges from the one who looks. More like the light of the oil lamp, of the burner, than with electric light. A light that must be placed on this side of the camera, nourished by a sort of inner sun, of stove, of blaze, without which the photographic image results a miserable clone, an opaque, lifeless duplicate of what is out there moving, vibrating. Without that light, everything remains dark, hidden, completely invisible. Without that light the bird flies away without letting itself be caught. The photography depends solely of that light. That is why many reporters of borrowed eyes and false mind have not been able to see what you have seen, nor many artists of dark glasses and hiker hearts, and they both return from those places bitten by the insects, with their boots filled with soil but with nothing to show, with an empty bag.

But let us say that they were really your eyes, Juan Carlos, that it was your camera. Even so, the merit is hardly yours. You know that well. Someone before you looked with identical curiosity and tenderness at those sticks, those stones, those lianas, those barbs. Someone before you enjoyed the communion with roast sweet potato, participated of the wild Eucharist of the pork slice, of the fried green banana served next to the humble altar of the scented firewood stoves, and received, before you, the courtesies, the offerings, the familiarity of the simple people from the mountains. Someone before you, without requiring the camera, made all those all those portraits and fixed forever on paper all those smiles of warmth, of sympathy, and also the profound wrinkles and grimaces of their loneliness, of their abandonment, of their poverty. Someone who, however, more than a century ago already wrote many times the word hope, the word fatherland. And discovered all of a sudden, with ashamed heart and full of tears, what you have seen now and Columbus greedy eyes could not have seen, nor the meticulous eyes of the Baron von Humboldt. Only the one who couldn’t sleep because the night was beautiful and heardperhaps the one only time among us the male lizard keekeeing. Who else could have listened to it?

Behind your camera, behind your eyes there has always been someone. And not only the illuminated eyes of the small José, our first and only visionary. Shortly before him, along those same routes, the utterly terrified eyes of a runaway slave also saw with joy the salvation of a ripe mango, of a creek, of a complicated path capable of confusing the course for the pack of hounds. A trail that perhaps sometime before was opened by the rapid step of a native Taino Indian, also fleeing from the arquebuses, the cross and the sword. Indeed, many eyes have seen these places. And then they have turned their glance aside, they have deflected it. Or have decided to look at it from the jeep, or through the kaleidoscope of exoticism, of the bucolic patriotism. There have always been more than enough eyes, and it is impossible now to tell the detailed history of those glances.

So none of us can boast of being original, of looking at these things for the first time. Not even our first men could. And I am not speaking of the eyes of God or anything of the sort, although we should not discard it. I am speaking of something apparently simpler: of the ancient eyes of the jutía, of the majá (a kind of snake), of the sijú, of the arriero (birds); of the always vigilant glance of the rooster, of the vulture. I am speaking of the minute eyes of the rosemary, of the bledo, of the escoba amarga (plants); of the imposing eyes of the jagüey, of the sabicú; of the protecting glance of the yaya and the guayacán (names given in Cuba to different trees), of the palm tree, of the ceiba. Weren’t they the first witnesses? Haven’t those numberless eyes gradually educated your glance?

Let us say it in another way. You have not been in the mountains just to take a look, to pry, to take this or that tourist picture, nor to stealthily deprive them of the intimacy of their treasures and then receive the applause of the city. You have been there to share, to openly evidence your wishes of belonging, of becoming a part of, of being from there. No matter if it was only for a moment. Nor does it matter that you also belong to many other places. Because one belongs to all the places that one loves. It has been the intenseness and the sincerity of that wish what has granted you the honor of the immediate membership. And in these times when the artist boasts of detachments and coldness, your gesture is a comforting statement in favor of plain feelings and belonging to a place. To a small place. You enjoyed not having been received there as a stranger. You went there to look closely, to verify, to touch, to hold with open eyes what you had heard of, what someone had written in his Diary a few moments before his death.

You went there, not to take but to give, to thank for, and you have received, in exchange, the blessing of having looked. Because what these photos express is not so much the certainty of having been there, of having looked, but of having been looked at, of having been recognized. The fact that those eyes glanced at you. That is your reward.

Visiting such places brings a sense of connection and understanding. It’s like finding a piece of yourself in the vastness of nature, a moment where you feel truly seen and understood by the world around you. Just like the mountains stand tall and majestic, you too feel a sense of strength and belonging.

Moreover, it reminds you of the importance of genuine experiences and connections in life. In this age of digital overload, we often forget the value of being truly present in the moment, of soaking in the beauty and wisdom that surrounds us.

Speaking of genuine experiences, if you’re ever looking to cancel your timeshare in Arizona, you might want to check out https://canceltimesharegeek.com/arizona-timeshare-cancellation/. They offer valuable insights and guidance to help you navigate the process smoothly.

You have listened to the great teaching and now you can repeat it: In the mountains, I am mountain.

Orlando Hernández

Havana, December 3, 2008

Artworks

White Ceiba tree

Juan Carlos Alom 2008We wait on the clear mountain

Juan Carlos Alom 2008Sticks

Juan Carlos Alom 2008Young Ceiba

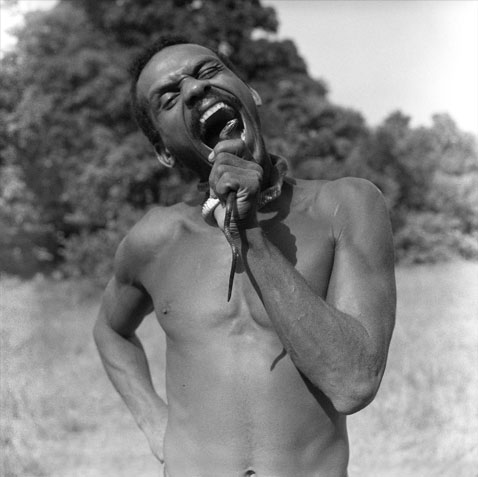

Juan Carlos Alom 2008Man with Snake

Juan Carlos Alom 2008Artists