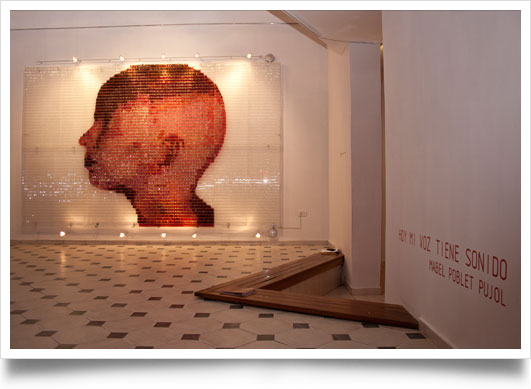

Today my voice has sound

Mabel Poblet, herself and the other (or red as strategy)

Mabel Poblet’s most recent works evidence the ripening process she has been experiencing in her years as a creator which, to tell the truth, are still only a few, although certainly intense ones. Her creations testify to a harmonious confluence of preceding searches, of ideas that at times had only been insinuated. To no one is it a secret that an important weight in her work is the reference to herself, be it open or subtle. There are those who have even said that there is an equivalent relation between her living experience and her creative process, and those who think that way have the right on their side, since Mabel is self-referential both in form and content. However, the art-life relation is not present in her from Beuys point of view but through a concept of art as catalyst of her experiences, feelings and wishes that enables her to maintain an homeostatic status with the surrounding world.

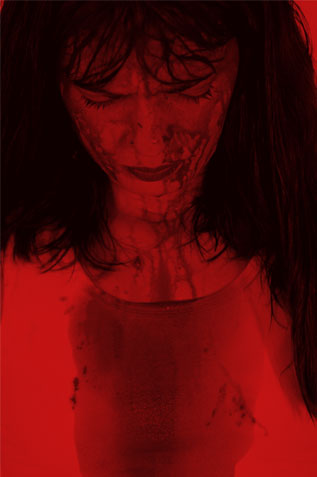

Mabel calls us to a virtual and real introspective, toward an unraveling of the human being’s biological and psychological dimensions. She puts at the viewer’s disposal her own ghosts, which could be anyone’s , since none of us is exempt of the restlessness caused by the need to maintain balance between the inner universe and external laws, whether called social conventions or human relations of all kinds. The distinctive signs will be the blood and its inherent color, red. Red has ambivalent and antagonistic cultural meanings. It indicates danger; in the banking language it represents debts, but

it is equally associated with the color of passion, and in China with vitality and good luck. Politically it is linked with the ideas of the left. Blood, in turn, may be life and death fluid at the same time. Its own function in the body, of carrying both the oxygen and the impurities of the body, makes it worthy of that categorization. Blood has been assumed by many cultures as purifying liquid. In the Bible we obtain forgiveness of sins through the spilling of Christs blood, or in the religions of African origin it is used as method to clean the parishioner; in pre-Colombian peoples blood was offered to calm the fury of some deity through human sacrifice and thus maintain natural balance. Blood can also be the vehicle to atone for personal obsessions. That is why in the piece Libation, the act of bathing, i.e., literally of cleaning, is connected with receiving the blood, or metaphorical cleaning. The fact that neither blood nor foam contaminate mutually in spite of coming together in the same space meaning that they are formally solved so as not to have direct contact has to do in some way with the power relations established among individuals; ideologies that do not mix, incompatible characters, irresolute tensions that produce silencing and spaces of exclusion. In these works Mabel uses her personal experiences as a form of approaching the more universal issues concerning any human being. But if previously this reference to herself appeared as a document, now her presence has a more poetic nature. The relativity of concepts, but above all, the circumstantial nature of power relations are ideas she handles with regard to phenomena like the (in) communication or the link between life and death, natural and artificial, biological and psychological.

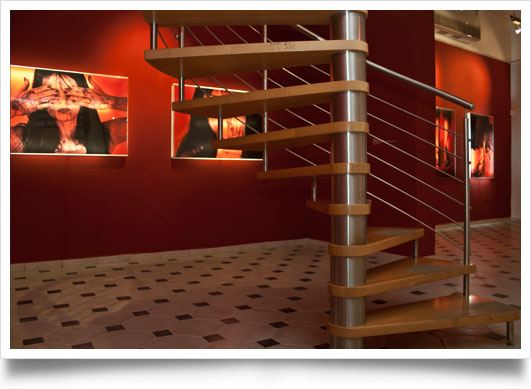

Contrary to what one might think, Mabel’s work is not aggressive, at least not explicitly. It does not allude to physical violence, and although its existence cannot be denied; it is of psychological, more evasive, but equally dangerous nature. Her images are beautiful, constructed with a visual nature where the concern for a formal impeccability is noticeable, but which, notwithstanding, contain a message at times coarsely realistic. Even when a bloody pair of legs or face may appear, they do not extrapolate the theatrical dramatic quality of the event itself, but appear ambiguously, in a quiet way, without producing alterations in perception. The viewer may observe these scenes even with pleasure. The artist’s intention is not to generate states of horror or rejection, but rather to convince the visitor to become a co-participant of her experience. That is why she does not take sides either; she just focuses on presenting, because Mabel is not interested in using the judge’s robe but in saying what there is to say, and at the same time in creating a space of comfort. The modus operandi of this creator might be summarized in being indistinctly the hand that takes up the dagger and the one that heals the wound.

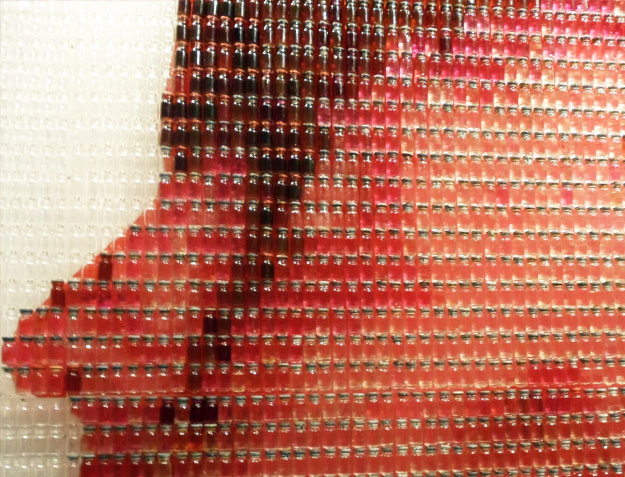

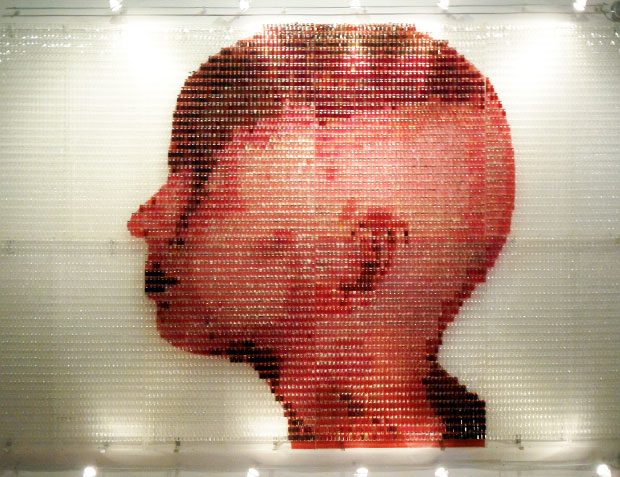

We likewise see how she has broached other art forms and moves at her ease between photography, video, installation. The technique of serigraphy on acetate is no longer omnipresent, although this does not mean she has abandoned it. It catches the eye that Mabel’s works are apparently micro worlds, each one with its own laws and ostensibly autonomous; and I say apparently because the interpretational wealth obtained by mutually linking them is comparable to the way in which the organs are connected in the human body. The link established between the parts and the whole has been part of the form of expression of this artist. Not in vain has she appealed to the figures on acetate that work as independent entities and that, in turn, are made to come together as small fragments of a larger image. In the piece Ana, 2011, she avails herself of this same resource, but replaces the acetates by injection bulbs full of red liquid. The image is hers, but assuming the identity of a woman with leukemia, a change that abounds in the idea of the ambivalence of blood, which here becomes reason of life and death. The fact of becoming an expiatory element is a new aspect of her work, which until now had been quite autobiographical. Their experiences overlap, enriching the representation and thus creating a new identity. This piece extends the range of her creations, because now she can assume others’ stories as her own and take advantage of the semantic wealth of this plurality of events to be told.

Mabel’s work has succeeded in articulating the ideological and aesthetic premises of her preceding works with new concepts of the art event. Using self-reference as cornerstone, she reveals concerns about the nature of man. Concepts like power and communication are part of her most recent pieces. She likewise stops on the relation between the antagonistic pairs of absolute and relative, life and death. In doing this she utilizes the symbolical possibilities of two elements that become essential in the discursive aspect, which are blood and red. Formally there is also evidence of an inclusive position, since she assumes other art forms as way of expression. We are therefore in the presence of a qualitative leap in the creation of this young artist. The road is still long, but Mabel already predicts a promising career.

Chrislie Pérez

Specialist, Villa Manuela Art Gallery

Artworks

Fluid

Mabel Poblet Pujol 2012Ana (detail)

Mabel Poblet Pujol 2012Talk to me

Mabel Poblet Pujol 2012Running away is no good

Mabel Poblet Pujol 2012An instant of happiness

Mabel Poblet Pujol 2012Libation

Mabel Poblet Pujol 2012Your last caress

Mabel Poblet Pujol 2012Libación (detail)

Mabel Poblet Pujol 2012Artists