The origin of a myth

BELKIS AYON. The Resurrection of the Marked Bodies

Body marks are always profoundly enigmatic. They usually refer you to voluntary or involuntary traces traces in the end that can produce multiple readings.

When one examines the work by Belkis Ayón, many are the attributes that favor the meeting with worlds of silence and mystery. The artist created a personal and unmistakable universe, characterized by multiple ethno-cultural traces of gender and ancestral nature. Now we could think that black and white were premonitory of a state of restlessness that was to end in disaster.

In her works, transfigurations are one of the most significant elements. It all derived from the permanent game with the matrixes and the surface of the marked bodies. Mutation is one of the revealing qualities of the unprejudiced treatment of the human figure based on the myth of African origin. It is a visual procedure started by Wifredo Lam in twentieth-century Cuban art, using syncretism for representations based on santería. Perhaps the most favored images in this regard were his combined forms of a woman-horse, a hybrid creation that seemed to summarize a human-animal interaction belonging to the mythical aesthetics of the magic-religious systems of beliefs. Similar references appear in his major piece The Jungle, a true cultural synthesis of Caribbean identity constructed from the perspective of the superposition and coexistence of visual interweaving.

The work by Belkis Ayón took those basic elements from ñañiguismo, a closed, masculine sect that created a much soberer, austere and much more enigmatic world of references. The artist broke the barriers of the abakuá silence through the body, leading us immediately to the flesh, that zone of contact and protection bearing both visible and invisible marks and tattoos. The flesh is that sensitive border, that skin barrier that encloses the I and limits it before the other. However, in the piece Arrepentida (Repentant) the authoress has said a woman tears her skin as symbol of the ambivalence between what we want to be and what we really are. The skin can also be a deceitful contact zone, the skin can mutate and transfigure.

This statement reveals the symbolical force to be assumed by the body in her work, and particularly the skin as epidermis, metaphorically changing. There is an essential difference with the work by Wifredo Lam in this way of doing things. The marks of hybridization do not appear in the mutant synthesis between the human vegetal and animal nature of the bodies. In Belkis Ayón, the practice is superficial, and the bodies act symbolically through their transfiguration, without losing human corporality. This element of her art discourse nominalizes a poetics of the body from an essentially philosophical and existential angle. In his regard, Belkis Ayón’s work opens to a deep critical reflection on the human condition, which far exceeds any reductionism to the elements of the world of beliefs of those who, coming from Calabar, are known in Cuba as carabalíes.

The authoress herself would say that the abakuá theme is going to be for some time the starting point, the pretext for the comparisons with life. This position indicates the ethical appropriation contained in Belkis Ayón’s art intention, whose penetration into that forbidden sphere of the Afro Cuban religiosity was basically through the intellectual path opened by Lydia Cabrera, Fernando Ortiz and Enrique Sosa, studious of this theme in different moments of our century. This type of approach, almost imposed by the prohibitions established for women in the sect, turned the artist’s glance away from the elements of the ritual or of the practice itself, in order to focus on more conceptual and symbolical aspects.

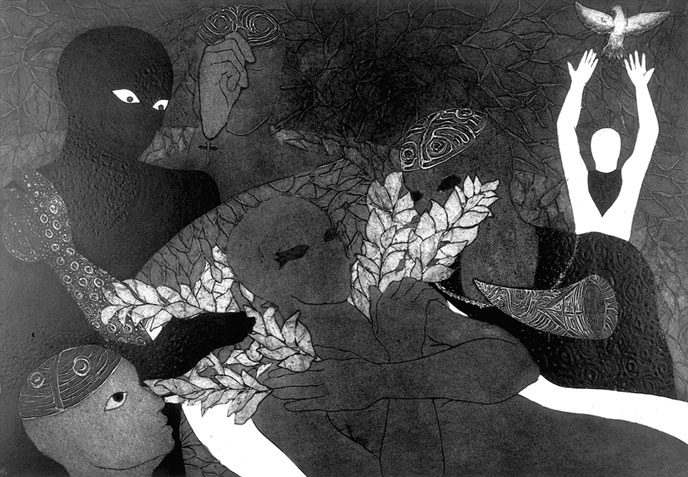

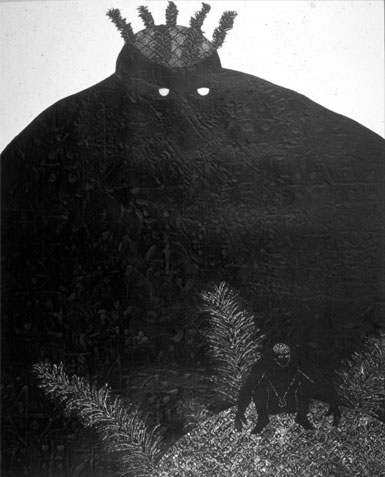

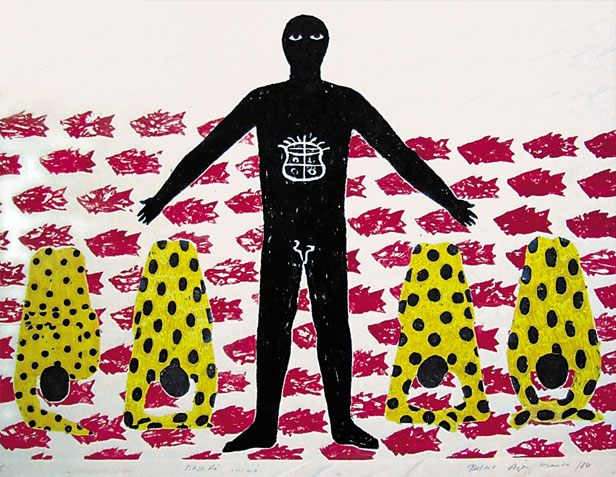

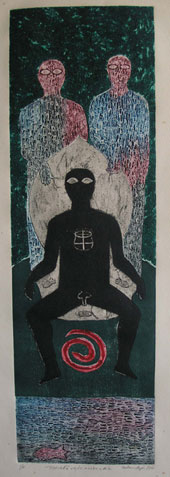

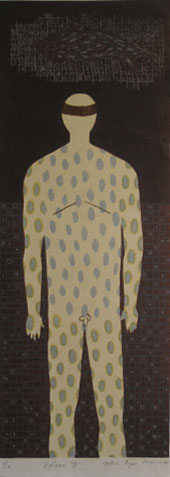

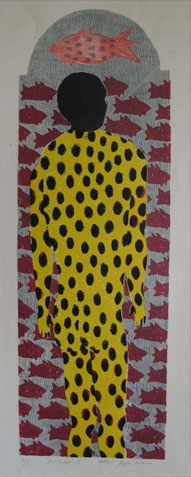

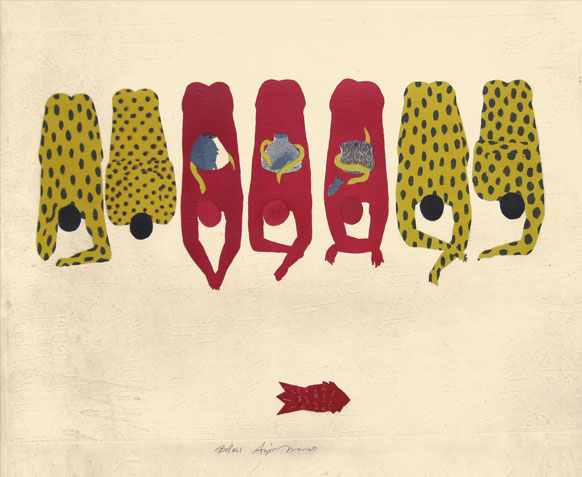

The human body was used by her as pretext for that search, which in terms of art implied overcoming a limitation in the representation of the human figure which she had since the juvenile years of drawing from nature. Her bodies are archetypes, cut-out silhouettes that contrast against a background, always with great mastery the colographic technique. The essential in the treatment of her figures escapes from the details that humanize them to find a place among the elements that transfigure and transcend them. It is in that metamorphosis where the greatest effects of preservation of the mystery covering the myth are achieved. The magic world and the hiding zones that wrap up the practice insert themselves over the bodies of Belkis Ayón.

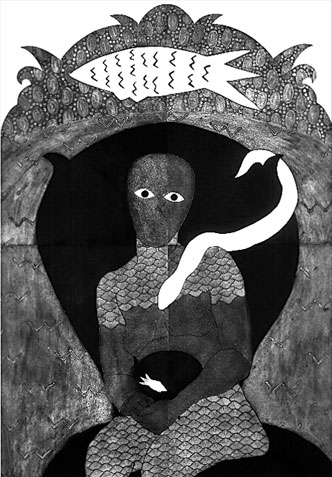

The relative lack of sexuality of her figures is used by the artist as a strategy to violate womens exclusion by way of the transvestite attitude that equalizes the bodies from the hybridization of their camouflage. It is in this dimension that the body acts as vindication sign in the generic perspective. The siege is not broken by the apparent changes provoked by the disguise. But Belkis Ayón’s work went beyond. The feminine body silhouetted by her matrixes was associated by the authoress from the first moment to the stigma of Sikán, the woman-victim, according to time and the legend. Like the Eve condemned by Christianity to serve and suffer because she was the protagonist of sin, Sikán was excluded because she had revealed the secret. One and the other, each one in her way, possess an anti-segregationist loading energy. To penetrate that forbidden zone from a self-referential experience is one of the great challenges of Belkis Ayón’s work: It is true that I am the model of my figurations and that they accompany me in going from one state to another continuously.

In this regard, Belkis Ayón’s work, which she never agreed to affiliate to the feminine trends, deconstructs the code of genre from two essential aspects: the mythical-symbolical, based on the ontological ground of ñañiguismo, and the artistic-representational one as essential element in the critical-conceptual strategies employed by the artist. In both cases the visual metaphor is constructed from the analogies.

The legend of Sikán refers that she approached the river Oldán to fill her jar with water, and the fish Tanzé, a representation of Abasí, swam into the jar. Sikán saw it, but since she was a woman she could not possess the abakuá secret, and therefore they decided to kill her. The event became a foundation of the belief, and Sikán’s image appears transmuted through the goat during the ceremony, whose death serves for the reconstruction of the legend. In The Sentence (1993), a black figure with small, round and very white eyes carries on its shoulders a goat whose four legs have been tied, and from the ropes hangs a small figure of a fish as talisman. The Sikán/Tanzé/Goat analogy reveals the mythical force of this triad.

The artist/woman appears in the painting space in the form of a summary image in which all of us who knew her could identify her, because she was betrayed by those big, almond-like eyes that characterized her. She was there in the forbidden space, but how? In the metamorphosis of the mutant skins that served her as clothes. Her indicative eyes appear mostly empty and absent, at times penetrating, elusive and questioning. Faces and bodies seem reversible and operate as screens for new concealments, for other profoundly hidden mysteries.

It was undoubtedly this zone of religiosity that Belkis most sensitively exploited in her art poetics. It was probably the one that produced the greatest impatience in her. Interacting with a knowledge that was full of impediments of representation led her ever more to a communicative formal and aesthetic art synthesis. Thus, her work was loaded with the hermeticism of its reference. In front of her engravings one feels the rare influx of the unknown, solved in art in very efficient manners.

Certain abakuá attributes like the baton, the rooster or the fish reappear in different works in very peculiar form. The pyramidal structure of the works on occasions recalls the ancestral nature of the forces and the structure of power. Among the animals, there is abundant presence of the snake, which remits to that African worshipping nature of such primitive and magic force; to the earth and to the depth where the magic forces of mystery hide. The atmosphere achieved in each piece completes the effect. Belkis was a master on the backgrounds on which her figures were cut out, backgrounds that show that infinite laboriousness of the expert colography, always in search of a new experimentation.

An apparent chaotic order is revealed in some pieces. Like Ticio Escobar, Belkis knew that myths are sufficiently protected, and that trying to penetrate them is not worthwhile. The artist does not deconstruct them, but appropriates them, and in the act of manipulating them discovers their most far-reaching values in the ethical and human order; in this regard she found an excellent reflexive, critical and symbolical platform in the abakuá religiosity. That is why her pieces impact and disconcert. The tireless searcher will not look for terms, phrases or denominations coming from the ñáñigo language, or from the name of its deities, attributes or drums. There were not the references Belkis used to build her nine-year long, solid and monumental work. Now we can realize how intensely she must have lived and worked to have her name become essential in contemporary Cuban art with only 32 years of age.

She undoubtedly appealed to key elements that are genetic in her work: concealment, exclusion, protection, brotherhood, fraternity, magic, myth, ancestry. Perhaps two aspects of the ritual left a sensible trace in her work: the ireme and the rayado. The former covers the body and is the incognito image of the ceremonial; the latter is a procedure of trace and signature on the drums, on the floor, on the objects. One and the other refer to the mark and the covering up, two keynotes in Belkis Ayón’s work. These terms act as a metaphor of symbolical transmutation on the body, which thus becomes coded by the designs of the forces covering and traversing it. The body was votive offering and tribute of her work of art.

It is precisely the ambiguity of her skin-headed women of apparently tattooed bodies that completes the enigmatic effect. As if they wore elastic Lycras, these images transform into figures of confusing skins that serve as camouflage to enter the forbidden spaces. At times, like in an Untitled piece from 1996, the body detaches from its apparel like a snake that would change its skin. A scaly skin that apparently stains the image of the labyrinth, which appears in several of her works.

An important element of the symbolical far-reaching effect of the figures is their penetrability. The traversed silhouettes reveal the vulnerability of the body in the face of the myth. Other times, certain parts of the body are replaced by symbolical codes of great significance, like the form of the fish in the place of the eyes. The fish is a key sign, the supreme deity of the abakuá, who appeared to men in the mythological form of Tanzé and is represented in the foundation drum called Ekué, which contains his divine voice.

By Yolanda Wood

Artworks

Untitled

Belkis Ayón Manso 1996Asleep

Belkis Ayón Manso 1995I gave you the power

Belkis Ayón Manso 1993My soul and I love you

Belkis Ayón Manso 1993Our Duty

Belkis Ayón Manso 1993Repented?

Belkis Ayón Manso 1993Ekwé will be mine!!!

Belkis Ayón Manso 1986They adored the guiro

Belkis Ayón Manso 1986Nasakó initiated

Belkis Ayón Manso 1986Nasakó watches day and night

Belkis Ayón Manso 1986Ndisime II

Belkis Ayón Manso 1986Ndisime I

Belkis Ayón Manso 1986Syncretism I

Belkis Ayón Manso 1986Syncretism II

Belkis Ayón Manso 1986Veneration

Belkis Ayón Manso 1986Artists