R-exist

Therefore I exist

To exist. There we have a word full of mysteries. Is it only -as defined by the coldness and extreme objectivity of dictionaries- the fact of being in the world? If so, why do human beings rethink it and define it over and over again?

We could say that to think about existence is an almost inherent quality in the human being. However, doing it from art multiplies the implications of the term while endowing it with a perspective that is closer to subjectivity.

Ernesto Rancaño offers a very personal view of existence. According to him, it could be defined by those elements -apparently incongruent and with autonomous meaning- that for dissimilar reasons converge in specific spaces and times. It is a sort of organized chaos, a puzzle where each piece has its function. That is why the works that make up this show have a certain conceptual sovereignty and act like a micro cosmos in that macro space of the gallery. Each one expresses itself and in its relation to the others, because it is this very relation that enriches the specific universes to which they refer individually.

Nevertheless, this more far-reaching idea of existence he pretends to offer is mainly based on those aspects that define him as a man, as an artist, but above all, as a social being. Rancaño is convinced that one of the possible ways to understand existence is the relationship with the other. Concepts then appear linked to the whole emotional intensity surrounding our lives, as well as to the feelings that nourish us like a blood torrent. Love, whether to the family, to friends or to the spouse, is a recurrent theme in his discourse. That is why the loneliness-company antagonistic pair is also evident in the pieces, as part of a discourse structured on the basis of the need of another to complement our identity.

To a certain extent, it could be said that in this show Rancaño evidences ideas tackled by him in exhibitions like La carta que nunca te escribí and La mitad de mi vida. In the first place, that tendency toward the object that has undoubtedly characterized his plastic production in recent times. But he equally handles aesthetic premises like the idea of cyclical, dual, the minimal language, the chromatic soberness, and up to a certain point, the use of absurdity as wink to involve the spectator with his postulates.

To re-exist becomes a more complex matter. With the inclusion of the prefix “re”, he alludes to that ambiguous space of the possibility of another existence. In what sense does he refer to the possibility of existing again? Not in the physical and tangible dimension, undoubtedly, but -and this is the most important thing- in all that concerns the inner universe of the human being. Re-existing then appears as an attitude of resistance. It is the materialization of that kind of anagnorisis in which the individual becomes conscious of his capacity to reinvent himself.

Chrislie Pérez

Havana, April 2013

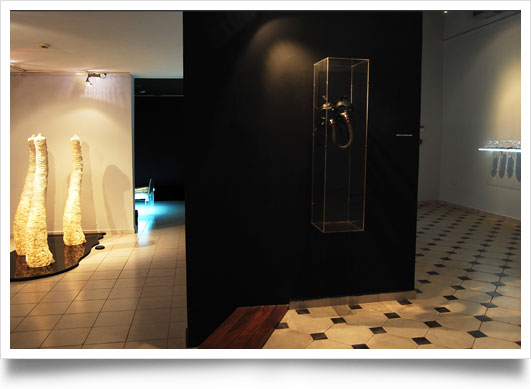

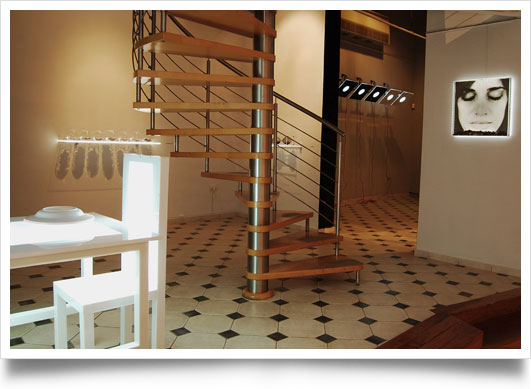

Artworks

Post-World Love

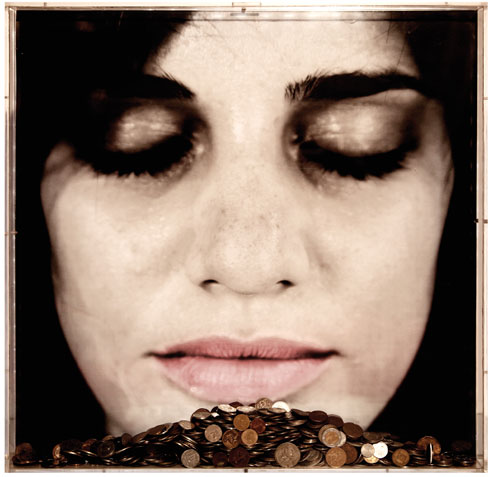

Ernesto Rancaño 2013The Wealthy Man

Ernesto Rancaño 2013Closed Sky (Persistence)

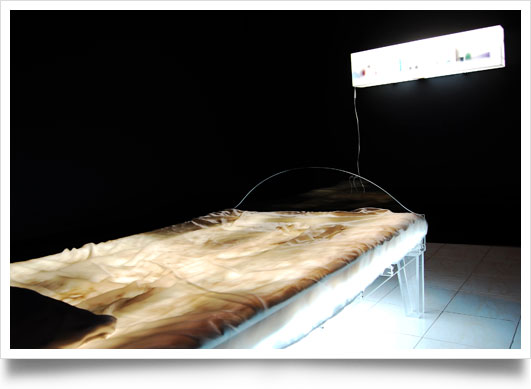

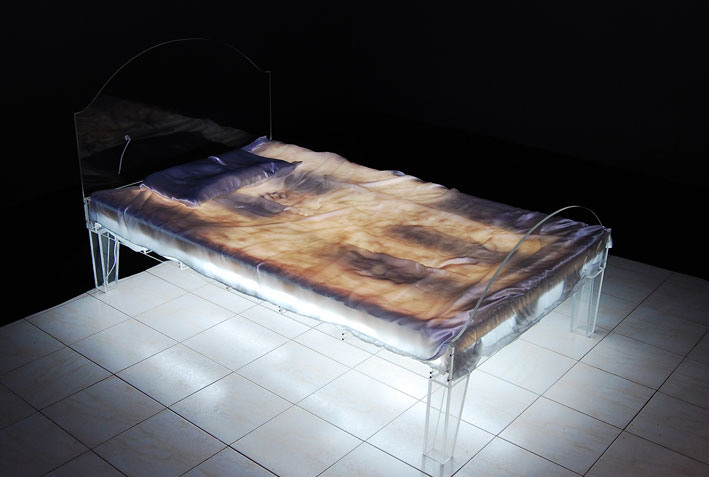

Ernesto Rancaño 2013Bed of Light

Ernesto Rancaño 2013The Wealthy Man (detail)

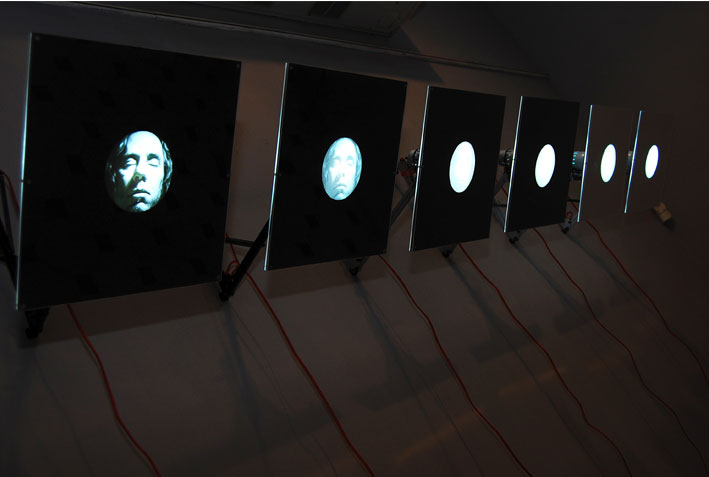

Ernesto Rancaño 2013Existence

Ernesto Rancaño 2013Lunar fish (Mabe)

Ernesto Rancaño 2013Detained Drawing

Ernesto Rancaño 2013Oblivion

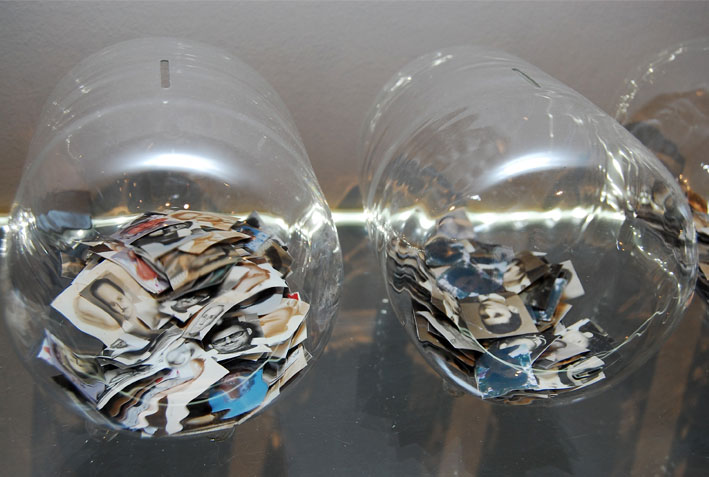

Ernesto Rancaño 2013I Insist

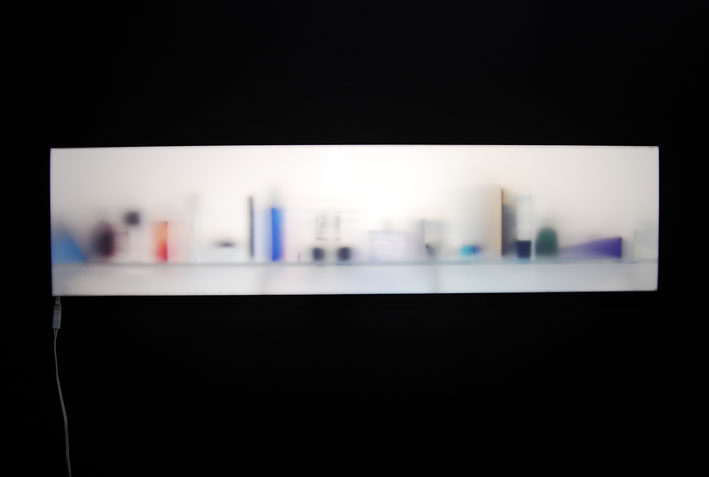

Ernesto Rancaño 2013City d'Odor

Ernesto Rancaño 2013I Insist (detail)

Ernesto Rancaño 2013Artists