Divertimentos

Divertimentos

There are those who continue to prefer identifying drawing with the supremacy of the line, and painting with the predominance of color. In tune with what Charles Baudelaire specified in the 19th century, the distinctive feature of the true draftsman lies in the finesse, incompatible with the stroke. And color does not exclude the big painting but the drawing with care for the details, the insignificant details of the small fragments, where the stroke will always devour the line. (1)

According to such grounds, the looser, overflowed brush stroke and the live, contrasting pigments would be inherent to painters, while the austere palette and the licked brush stroke that does not overflow the space delimited by the contour lines would be consubstantial to the draftsmen. Pure taxonomy.

Avoiding the sectarian dogma up to a certain point, Baudelaire did not discard the possibility that the same visual artist would combine the colorific artist and the draftsman: the former, because of the dominion of the big masses; the second, by virtue of the complete logic of the group of lines. And his assertion was as categorical as balanced: one of these qualities always absorbs details from the other.

The practice has evidenced that some artists who excel in drawing have not enjoyed equal excellence when dealing with oil or other painting technique. They do not achieve optimum visual effects. In this regard, the very history of the so-called Cuban art can name more than one figure. But, of course, each rule has its exception(s). And one of them is named Cosme Proenza.

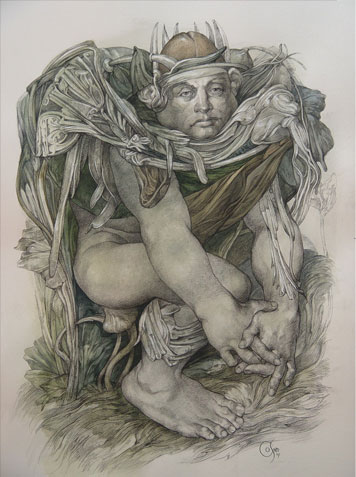

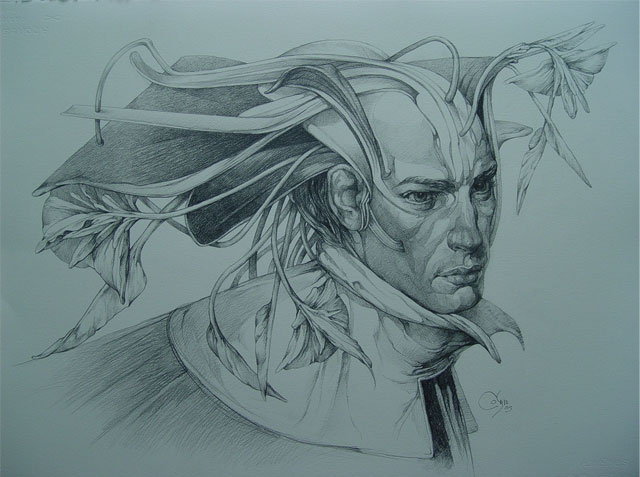

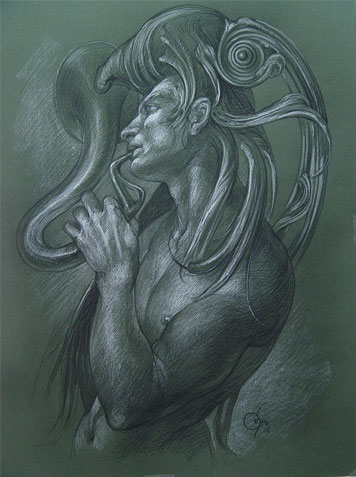

Not only because he can successfully handle those particular aspects of painting and drawing, but also because appealing to the mixed technique he works freely in what Juan Acha has called painted drawing: a kind of symbiosis that may be appreciated in this exhibition. Even though color does not usually go beyond the outlined parts, it grants diverse shades and volumes to the forms, with or without the scrap metal achieved by the ink or the graphite.

This exhibition points to a different relationship between painting and drawing, since some of the graphic works it has brought together are related to other canvases by Cosme exhibited at a different time and place. This is recalled by certain titles, like those of the series The Gods Listen. This is evidenced in the recreation of mythological themes and figures, particularly those emerged from the Greek cornucopia.

It is also asserted that drawing is the matrix for other expressions of the visual arts, the means for the sketches that precede the definitive work. Thus, an ancillary role is attributed to it. When these complex figures by Cosme are detailed, we discover in their background, generally a simple one, a shadowed area of stains or strokes that are frequent in the sketches. The fact that they are isolated figures, as if their physical and psychological attitudes were being studied as fragments or details destined for a bigger composition or scene, contributes to reinforce the appearance of a sketch or the transitory nature of those drawings. In this way, drawing would serve to produce quintessences, to the analytical operation in conceiving the art proposal.

Now, when we realize how excessively meticulous Proenza has been in these drawings, and we perceive the complexity of his unitary compositions, we start granting them more autonomous value. As to the rest, the proposal of the well-finished project as a work in itself is an issue already left behind in Cuban visualization.

Despite the heterogeneous origin of these works that do not belong to one series or motivation, despite the variety facial traces or face expressions, a common feature appears in almost all the exhibited works. It is no longer the link between painting and drawing. Neither is it the idiolect or personal way with which the artist conceives and unifies them. It is the delight in the characters attire: an attribute that individualizes them and distinguishes one from the other.

It would seem that even the human being, demiurge or deity, were the support of those winding, baroque, variegated and identity forms. The bodies naked or clothed hardly appear among arabesques that at first sight might seem decorative. Like Arcimboldo, the famous Italian Renaissance painter, Cosme would seem to melt also the anthropoid and vegetal natures in search of comparisons of elliptic apprehension. But he would also seem to flirt with the hidden data, not entirely suitable for disclosure.

Israel Castellanos

Art Critic

(1) All the references to this author were taken from: Baudelaire and the Art Critique. Editorial Arte y Literatura, 1986, pp. 31-32.

Artworks

From the series: Woman with Hat

Cosme Proenza 2005Untitled

Cosme Proenza 2005Untitled

Cosme Proenza 2005Untitled

Cosme Proenza 2005Untitled

Cosme Proenza 2005From the series: The Gods Listen (diptych)

Cosme Proenza 2005From the series: The Gods Listen

Cosme Proenza 2005Demiurge

Cosme Proenza 2005Theseus and Minotaur

Cosme Proenza 2004Orpheus

Cosme Proenza 2004Artists