Diary

Diary

Every language is an alphabet of symbols

whose exercise presupposes a past shared by the speakers…

El Aleph, Jorge Luis Borges

I have always thought it a strange privilege to know the totality of an artist’s work. I compare this circumstance to the imaginary possession of a virtual catalog raisonné where all the printed pieces of a puzzle are contained. If now, having followed Montes de Oca’s work for one decade, I were asked about its possible systematization, classification or division in stages or periods, I would be in an awkward position because, seen as a whole, it is a great treaty on art and life, some of whose pages have been torn off and discarded while others survived definitely.

The first impression when looking at his works more than a decade ago was a paradoxical mixture of indecision and surprise. Indecision, because I did not know what to decide: whether to speak or remain silent. Luckily I did not remain silent; I faced the dilemma of expressing what I thought because I sensed that there was something behind those unknown, strange pieces that attracted me and clearly pointed to a swift and sharp evolution. And so it happened…

In 1992, his first solo show was characterized by water: a terrible shower, one of the most intense of the nineties, threatened the opening event. By that time the art diaspora had decreased, while the weed kept growing: every month we attended a new show where glittering “stars” initiated themselves in the gallery space rite.

That afternoon, under a strong spot light, singer Orestes Macías interpreted one of the oddest songs ever written Bodas negras (Black Nuptials), a necrophilic love story where a lover steals the skeleton of his beloved woman from the cemetery to take it to the nuptial bed and embellish it with ribbons and flowers; very peculiar, but we had decided to give the exhibition that title. What we are describing took place in a Development Center for the Visual Arts, in between two paradigmatic exhibitions: El objeto esculturado (The Sculptured Object), in May 1990, and Las metáforas del templo (The Metaphors of the Temple), February 1993, a unique and complex period of contemporary arts in Cuba. The boring and unsubstantial dispute on the continuity or rupture of the art of the nineties as replacement for the astonishing eighties was starting at the time.

Today I cannot recall in detail those strange paintings, and I cannot cease to superimpose his present works to them, but at the same time I do not pretend to eliminate the daily creation I saw emerge during the curatorial work of the exhibition. Biomorphic, beheaded, dismembered beings run through by huge knives; it was an almost apocalyptical vision the one assumed by the painter. In Cuban art, Antonia Eiriz and Umberto Peña had gone far, but Montes de Oca planned to go beyond… Perhaps for that reason his models diluted and the possible references were rapidly exhausted; the artist somehow arrived at a point of no return… And in that precise moment, the unexpected happened: he had to retire for four years from the natural environment, the laboratory that Havana was becoming after the celebration of the Fourth Biennial in 1991.

Cuban art had gone beyond its Annunciation and was arriving at its Nativity; it had ceased to cook itself in its egocentric iron pot and was gradually sliding towards boiling in shining pans. While this was taking place in Havana, Montes de Oca continued his work in a city as artistically off-centered as Bucharest. The pieces from that period between 1994 and 1997 show an evident, but at the same time logical lack of orientation. All kinds of interesting projects emerged in those days; thousands of sketches accumulated, but almost nothing was accomplished. When he finally returned to Havana everything had changed. Cuban art was the target of gallery owners, museum directors and one or the other scoundrel disguised as patron of the arts. In the midst of that situation he continued his Diary; it had to be written at all costs, without fear, although he began that new cycle of his work in great fright.

This restructuring and his reinsertion appeared to be difficult, in a definitely transmuted milieu. In a certain way he was now a stranger in that swarm of art and artists he was again in contact with. A return entails putting together many objective and subjective elements which are not easy to convoke at the same time; it was a career he had started some time before and he was trying to reach the platoon up front. If Montes de Oca’s Diary had a material existence, we would start his Second Chapter right here.

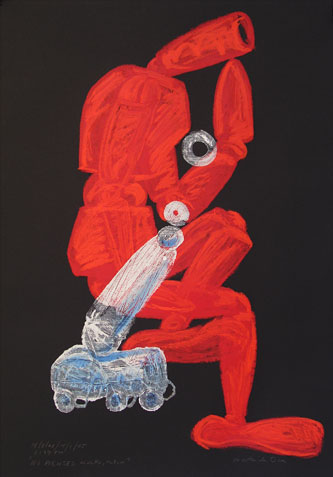

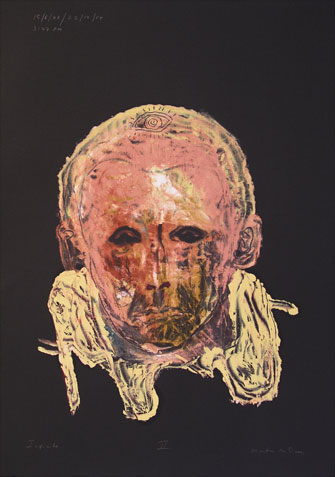

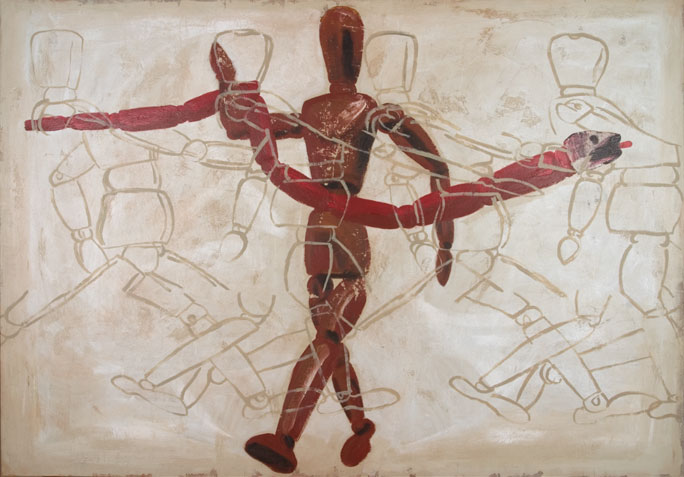

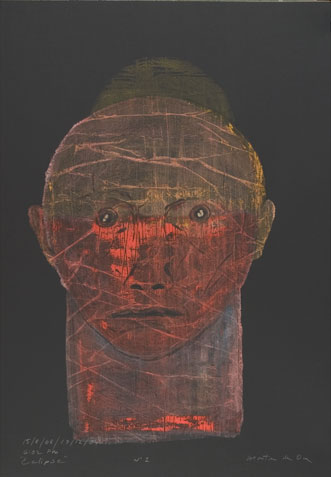

The presence and use of symbols in his work is not a recent event, it was a constant element along all these years. Some times he pictured us as monsters, other times he transformed us into a vulgar shoe or any daily object; later we were animals, more recently he has turned us into a mannequin-model that responds to his creator’s manipulation; at times he forces us to walk or run; if Montes de Oca wants to, he makes us stop our march to say farewell.

But not always is everything so evident. On occasions he takes us by the neck, other times he turns his back on us. Submitting ourselves or not to these codes that emerge from their own existence is one of the options; perhaps the other one is to consider them true riddles that keep an inscrutable secret. Whatever the decision is, we will be going beyond the threshold of a diary, his diary, giving turns to a finite sandglass that may stop anytime.

In 1998, in the catalogue of his exhibition El ultimo día (The Last Day), in Galería Habana, the artist published a revealing testimony that may well be applied to his most recent works.

“The delight I create in my work with the symbols makes me understand the relations between my analyses and their historical roots, and interconnect the cultural legacy to my experience (…). To me, the means is the work, and the process, the target.”

If to Montes de Oca the target the process is, in this way he will be revealing to us part of the secrets contained in his works. The question is not to appreciate a piece in itself to draw individual conclusions on each one; we have to go back to the previous one or go to the next one, to the ensemble, in order to discover his true intentions. Apart from that we must acknowledge that each symbol varies its meaning according to the context in which Montes de Oca has placed it.

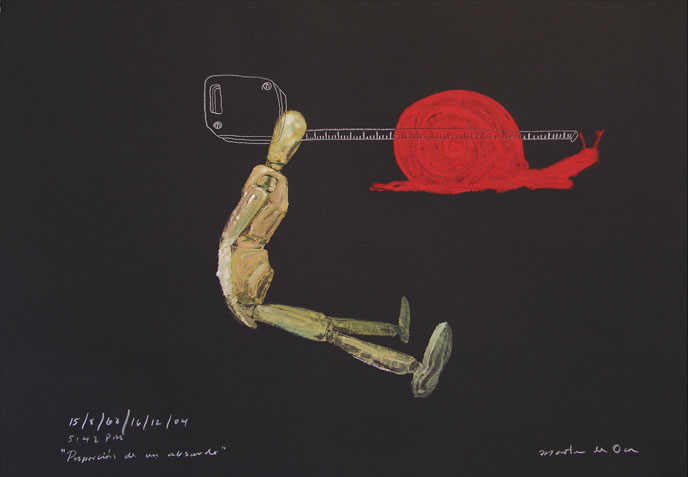

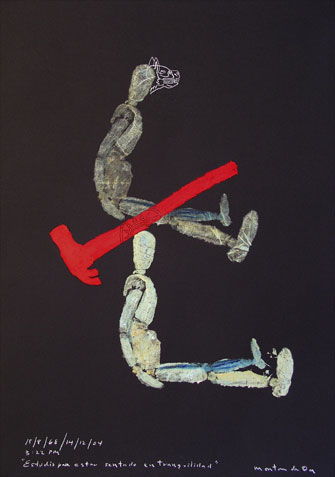

In Para andar en aguas oscuras (To Penetrate Dark Waters), 2001, the leit-motiv of the group of drawings and paintings exhibited is a small figure of clay, glass and animal gut, of the type employed in drawing classes in any academy of visual arts. It is not possible to verify if the artist represents himself through this now omnipresent character. When in 2002, in the exhibition El Ídolo (The Idol) at the Wifredo Lam Contemporary Art Center perhaps his most successful installation the artist placed wood and balls in the center of the hall, he had conceived a character through which he models and expresses his ideas in variable sizes. However, we still ask ourselves: what did that large mannequin symbolize? Was it a universe at human scale? Was it humankind with its eternal conflicts? Was it us…? In fact, it is not too important to reach forced conclusions; in this case the impact in the spectators entering and leaving the hall was more substantial. In the most recent pieces, the (dimensional) idol takes other roads, assumes new roles (even that of the anti-idol) and seems to guard the exhibition.

However, let us not fool ourselves. Montes de Oca will abandon him anytime. It will return to the corner of his studio when he considers that it already fulfilled its mission. In the meantime, let us await the upcoming events of the Diary… and, let it be.

José Veigas

Artworks

Hierarchy (detail)

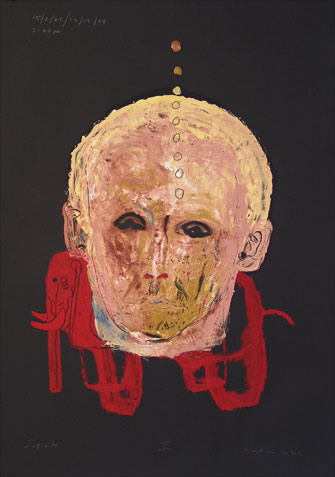

Carlos Alberto Montes de Oca 2005Herd

Carlos Alberto Montes de Oca 2005Origin of a Mutation

Carlos Alberto Montes de Oca 2004Proportion of an Absurdity

Carlos Alberto Montes de Oca 2004Don't drown

Carlos Alberto Montes de Oca 2004Studio to sit in peace

Carlos Alberto Montes de Oca 2004Extend to the infinite

Carlos Alberto Montes de Oca 2004Don't think much, act

Carlos Alberto Montes de Oca 2004Infinite II

Carlos Alberto Montes de Oca 2004Infinite I

Carlos Alberto Montes de Oca 2004The Bridge

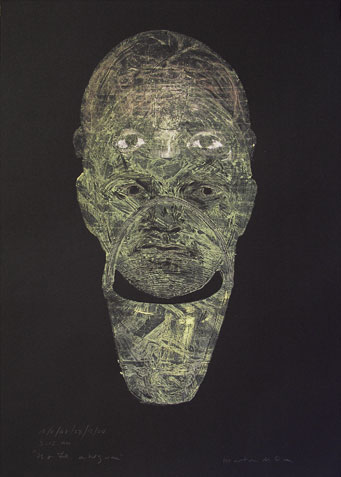

Carlos Alberto Montes de Oca 2004Eclipse

Carlos Alberto Montes de Oca 2004The road

Carlos Alberto Montes de Oca 2004The good bye

Carlos Alberto Montes de Oca 2004Artists