A place in the world

A place multiplied in the world

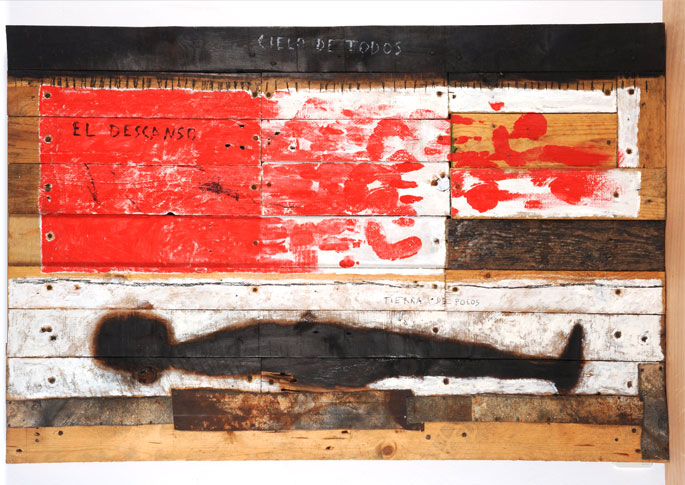

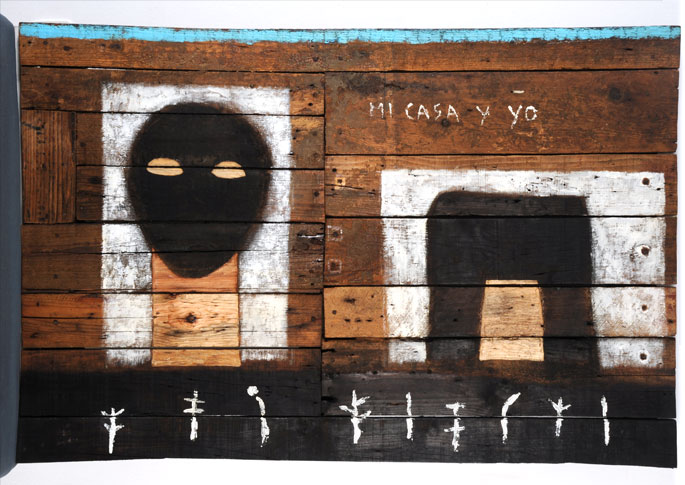

If something has characterized the work and even the art career of Roberto Diago, that is the non-acceptance of a unique support: zinc or metal plates, jute fragments; wood, sack fabric, linen, paper, cardboard, video and backlights have paraded before our eyes according to the needs of the project he may have in mind.

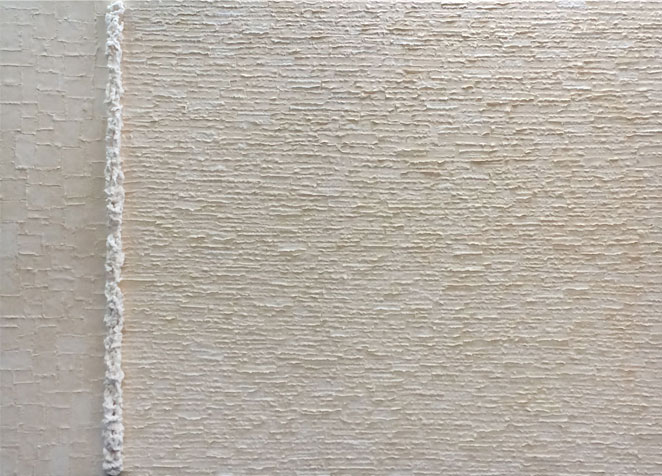

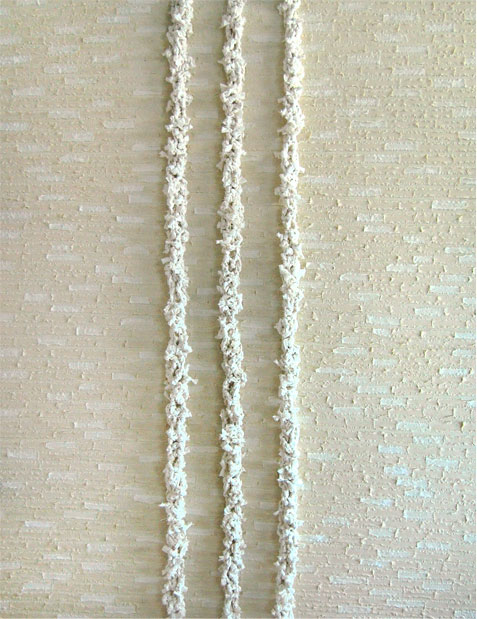

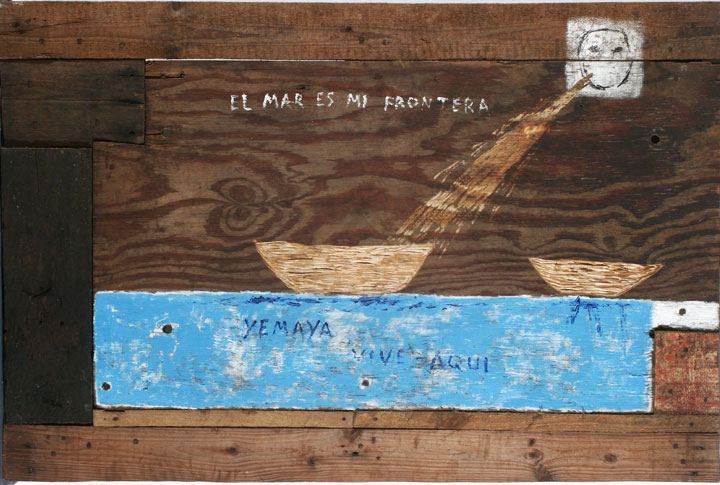

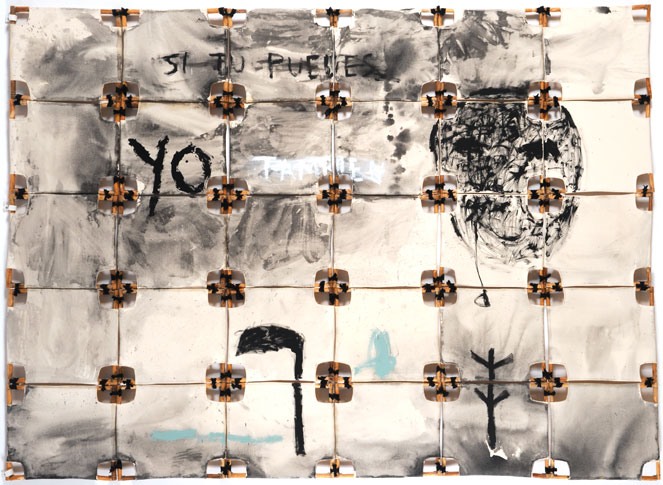

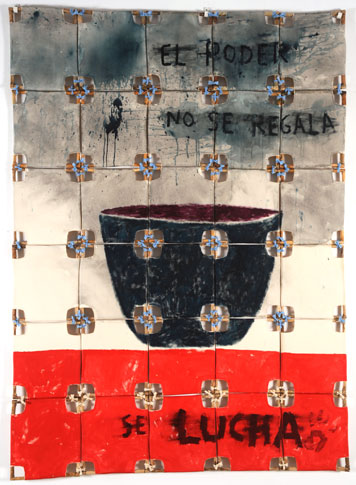

And when we think we have seen everything, he appears with something coherent and new. As it happens now. This time Diaguito appeals to two proposals: relying on the most classic minimal, he has constructed and lined up identical linen squares whose unique stretchers consist of small, well-cut and sanded branches joined together by fabric strips according to the color prevailing in the composition. Thus, he can construct a work infinitely or leave it in one small piece, granting it a certain charm as a multiple original. The other solution Diago offers us is the work on wood (something that is not new in him), but this time the paint or the neo-expressionist trace dilute to give way to the economic typification of graphics as concerns both line and text. His houses, trees and birds are incisions (lawn) he has carved into the wood, turning it practically into a matrix or wooden peg for xylography. As if he wanted to spread (reproduce) his hopes and certainties all over the place.

When we approach the pieces we are struck by a certainty: Roberto Diago knows how to deal with materials. He is capable of squeezing out their expressive capacities to the utmost. He makes them coexist in an excellent tension of fragility and solidity, of both a povera and a cool look; the bi-dimension that struggles to emerge and becomes a sculpture. He forces the materials to cast a vision of permanence and provisional nature without depriving them of one atom of beauty.

This exhibition has driven away a good many of his ghosts: ciao-ciao Boltansky. Bye, bye Basquiat. Good-bye Antonia. On the other hand, he has transferred his rights of speaker and tribune. I fail to see the margins or the aggressive social promiscuity, and the racial themes. This Diago is more inclusive. Perhaps the way of presenting the faces betrays his ever present obsessions, but nothing else. Only there.

It is a matter of common sense, and naturally of wisdom, to expose one’s arguments based on the observation of the most immediate world. Diago has done exactly that. Instead of getting lost in speculations or in old sophisms, he has individualized the notion of power. He has presented it as the incarnation of personal will, he has brought it to the premises of the morals (If you can, so can I), of the living above, as understood by Nietzsche. But much more interesting (and even heretical at times) if we look at it from the standpoint of Philosophy, is the fact that he has endowed the will with reason, turning it into something liable to be dosed and tamed. Arthur Schopenhauer summarizes it as follows: In mankind, the will, i.e., the natura naturans, succeeds in reflecting.

And this exercise begins by very domestic and daily elements: the house and the tree as foundation and protection. Cándido would say: We must take care of the vegetable garden. You may call it Oriental, African wisdom but I am also speaking of devices that are very dear to the poets of Orígenes and even naturally to a good many representatives of the second Cuban vanguard (Portocarrero, Amelia, Mariano), only that in these Diago pieces the almost pure and identical let us say sober lawn replaces the arabesques and the baroque of the former.

Diago seems to agree to Lezama’s words: In the center of every house there is a structure, a tree that turns the real into sacramental, into something that germinates. House and tree as founding units, from where all forces emerge. Adorable sites. Places in the world from where it is also possible to hit the mark.

Elvia Rosa Castro

Artworks

Me, you and the sea

Roberto Diago 2013Your soul's peace

Roberto Diago 2013For you, a little love

Roberto Diago 2013The strength of your soul

Roberto Diago 2013I like you like that

Roberto Diago 2012Inside of me

Roberto Diago 2012My home and me

Roberto Diago 2009Take me out of here

Roberto Diago 2009The sea is my frontier

Roberto Diago 2009Look at me (detail)

Roberto Diago 2009If you can, me too

Roberto Diago 2009Power is not given but fought over

Roberto Diago 2009Take me out of here (detail)

Roberto Diago 2009Artists