Four connection

Nostalgia does not kill

If I dig into my memories, I recall a house, a small house with the sea in the back; I see a staircase, a table and coffee, an indescribable coffee, not from Vienna or Paris, maybe from Bayamo or some unknown place where time does not go by; I evoke the walls, covered with paintings that still have not died, the figures and objects that dialogue with me, and I see a strainer that exudes my childhood, and a sad girl that awaits the arrival of the father by the window. Quite some evidence of faith that my memory recalls! I do remember, indeed, the studio-garage, and among so many fragments of who knows what lives, some recently painted stretchers and, in a procession, the varnished papers drying in the open air. And I see Nelson and Flora, who could do everything, and the two mischievous children – not more than any other children – drawing a route with no owner in the water.

Sometimes it would seem that nothing is the same anymore. It would suffice to ask and listen to the answer. We still have the Innocence; what is ours and human: the growth of these years and the health of one day. It should not amaze us then that those two children bring back time and offer us today their vision of the events, of the events that were and of those that will not be. Dressed as king and queen, the parents escort them, and all of them are in the picture, re-united as always for their exhibition.

In tune with the times, I will only say about the title that I would have preferred that of a classic bolero. This family of works comes from the affection, and passions usually exist in silence. At least for me, since I experience them in secret.

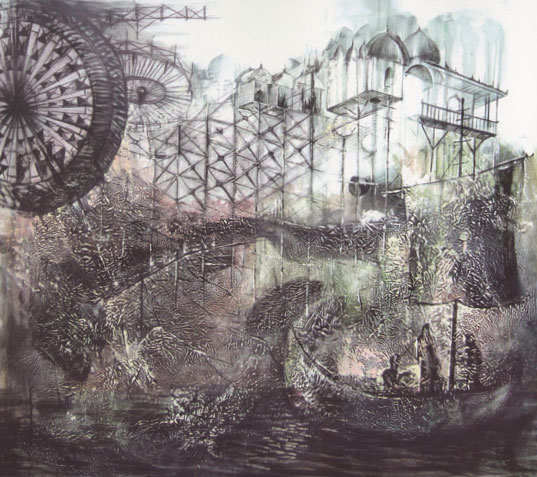

When stopping before Li, I am amazed by the textures with which she tells me a dream, the one of her fantasies. Sometimes as a sketch and almost always in a fog. It seems surrealistic, but it is a return of waters, of those free waters removed by the children. She has more than enough skill and the strength of a genius in her few strokes. In desolation, if she were to knock at my door, I would save her along with myself. Memories of a Hanging City and That Evening, in addition to other homesickness, doubtless numerous. Liang, skillful and confident in engraving – even capable of returning when out of breath -, revisits herself now to be born differently: violent atmosphere, not in darkness, which also lights, but in the density of her somber themes. She wants to tell us that the concept is her work, and she attains it in the form, and leaves us thinking of what we have not seen but imagined. Hatred, Envy and Uncertainty would deserve a place in the impossible ark of my appropriations. Both are correct in not wanting to appear.

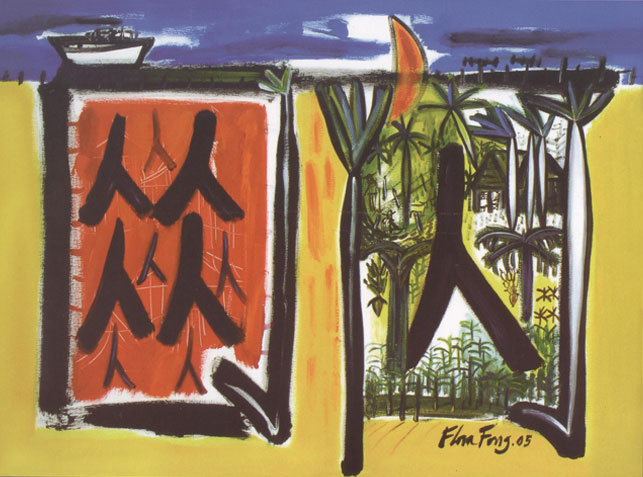

And I arrive to the territory of other knowledge: Flora and Nelson add quietly to this celebration, as one who lets others do, as someone who accompanies. She shares discoveries, he meditates and confesses. Whoever stops before Flora will see time go by – that changing moon, that light which is a clock, that immanent heritage, that Martí that peeps out, and in her calligraphy the ancestral worlds and a palm tree that is wind. Nelson, patriarchal and explicit, documents with thrones these revelations. They are thrones, on the other hand, that no one would seize, because in themselves they represent the story they want to tell us. I speak of symbols, of the fragility that power entails. If we read this installation correctly, now complemented with its flower version – meaning woman, couple, kindness and tribute – no explanation is required. Empty as they are, these intact thrones, full of remembrances, will remain forever linked to the memory. There is a mastery for teaching in the parents.

If other destinies existed, they are part of life, and chroniclers will tell about their joy or misfortune, including a painter. In any case, no matter how much they may try, nostalgia does not kill.

Omar González

Artworks