Nucleos of time

Walking on Stilts: An Answer in Times of Globalization

According to Fredric Jameson, a “lustfulness of the market” takes place in our times. A story like Harry Potter’s makes J.K. Rowling multi-millionaire; Paulo Coelho’s novels, with more than 50 million copies sold and translated into fifty-six languages, are recommended as reading material in several universities; Dali’s drawings produce considerable amounts of money in bazaar sales, as designs on hats, ties and even in shop windows, and thus, the modern ideal successively continues to deteriorate. Almost nothing escapes this cartography of voids of meaning where the standardization of culture many times obeys psychological reasons. Psychoanalyst Suely Rolnik has an interesting point of view in this regard: “Enjoying the richness of the present depends on the individuals facing the voids of meaning caused by the dissolution of the figures in which they recognize themselves at all times. Only in that way will they be able to assume the rich density of universes that inhabit them, to think the unthinkable and invent living possibilities”. (1)

In the context of Cuban art, Kcho is a polemic figure, because with his individuality he has succeeded in evading the usual antagonistic positions facing the phenomenon of globalization: the insistence at all costs on a reference to identity, on one side, and on the other, the exaggerated destabilization. His is a unique case: coming from Isla de la Juventud, with no higher studies and only 25 years old, he emerged in New York from one day to another. In 1991 his work became known outside Cuba through the exhibition Los hijos de Guillermo Tell (The Sons of William Tell) (traveling to Venezuela and Colombia), and the impact caused by his discourse of “the ephemeral” made him famous.

His idea of sculpture, separated from the ontological condition of the means of expression, turned his pieces into live nature where the artist’s hand scarcely intervenes. According to him, the material is not dominated, but it is allowed to evoke meanings based on its physical nature, whether natural or recycled. He offers with it a message of socio-cultural connotations, but his greatest merit lies when speaking of Cuban-ness in granting energy and organicism to the traditional elements and symbols that have been turned into stereotypes due to their indiscriminate use, and in returning their original value to them. On the other hand, his concept of space, in which he takes Lucio Fontana as reference, has contributed to make sculpture a traditionally drowsy genre in Cuba less rigid. His sculptures to be hanged or that may be perceived entirely from a single angle because of their degree of synthesis and in some cases of transparency are unique in the history of Cuban plastic arts.

Kcho’s latest exhibition in Cuba took place in 2002, and in it he found inspiration in La jungla (The Jungle) by Wifredo Lam. Here he combined the unique direction of the rationalist ideal of progress prefigured in Tatlin’s Spiral of Movement to the Third International with the diversified precariousness of the Caribbean context. The show was a tribute to the prominent Cuban painter for his contribution in attracting the Eurocentric glance to the art of the Third World.

Throughout the years Kcho has had to find the way to manipulate the same themes migration, utopia, identity, etc. under pressure of a double danger: to be absorbed by the market as an artist commenting on delicate problems of the Cuban reality, and by the way in which such questions have been projected from his discourse of precarious.

The objects of Cubans have been transformed in his most recent approaches; now, in addition to precarious they are threatening. Still motivated by the urgency of migration in his context, he refuses to leave the topic aside, and during 2002 he started the series Objetos peligrosos (Dangerous Objects). Here he uses as novel element of his proposals: the quills of the spearfish. In one of the versions, they are an allegory of the danger represented by the adventure of traveling; in another, the tensions that may appear in interpersonal relations. To Kcho, friendship is his amulet; that explains the poetic nature of some of these interpretations.

Traveling is something the artist does because he is compelled to, but which does not please him. That is why there is always a counterpart when he broaches the theme: the stay at home. Archipiélago (Archipelago), the series he started in 2003, alludes to the inevitable journey. A map of Cuba made up by a reduced fleet of small ships and three propellers that define Yucatán, Florida and La Española, displayed on an extensive area. The ships, full of constructions (lighthouses, electricity posts, etc.) refer to the contingence of navigation, to the constant flow of communications that interconnects the earth and without which we could not survive. However, the house is a constant in this story; without it no displacement could be conceived. This piece is like a synthesis of two important moments of the author’s tragedy: the favelas and the regatta, and Kcho made several versions of it.

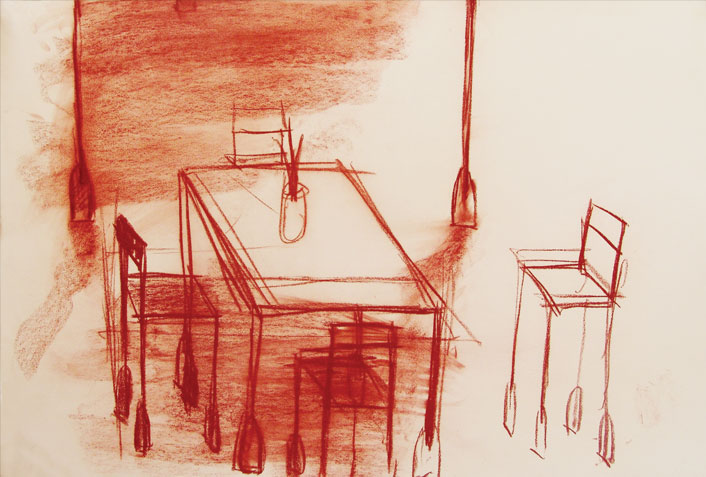

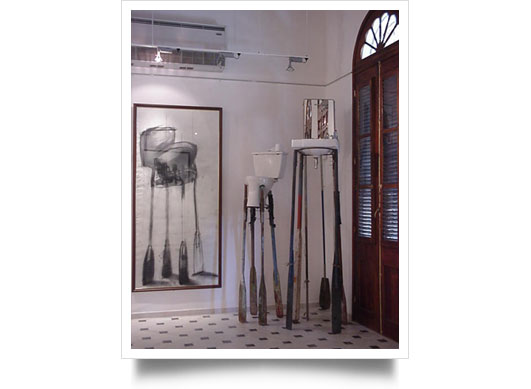

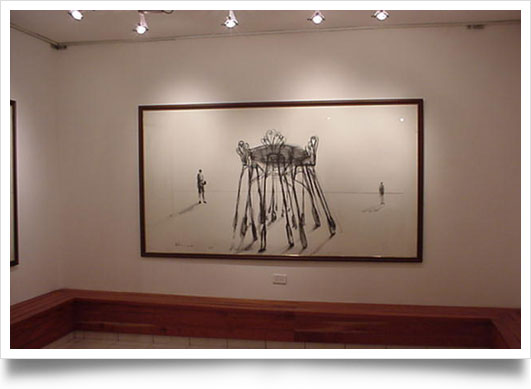

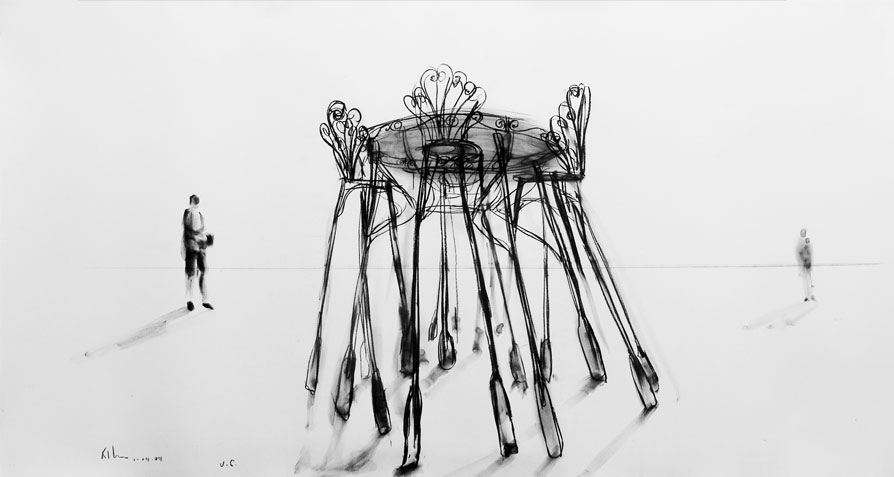

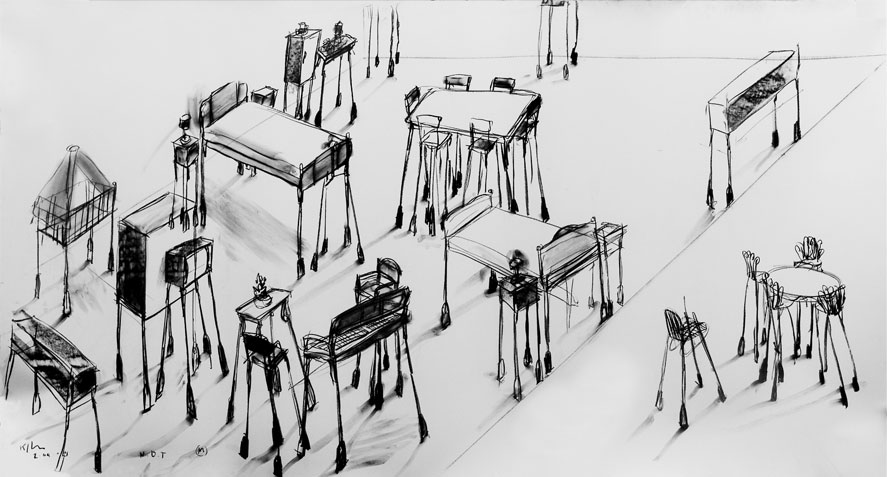

In 2004 the artist displayed Núcleos del tiempo (Time Nuclei) in the living room of his home in Miramar. The environment consists of an entire house arranged on top of oars. This one has been installed particularly with furniture and belongings from Kcho’s home in Isla de la Juventud. Friends, relatives and acquaintances contributed with the stage machinery. The piece has the bedrooms on the same level, so we may move underneath without great difficulty. Precariousness is still a constant here, and the fact that in Cuba several generations coexist under the same roof because of the difficult economic situation also becomes evident. However, although each one of these spaces is particularly dear to Kcho, the idea he wishes to transmit to us is not that this is precisely his home (it could be anybody’s); he is not a homely man, we say in our country, but these small places give us security, peace, warmth; they are those places where we are more ourselves, and which, in spite of it, many times we have to abandon against our will.

By placing the entire furniture on top of the oars that resemble stilts, the artist creates an allegory about the migratory phenomenon and its personal and group echoes. He proposes to assume the journey like another event in the midst of the present groups of problems. His attitude is that of one who returns from everything. Once more Kcho uses precarious objects to activate the connotation of these fragments of life, unforgettable because they belong to our intimate universe.

Núcleos del tiempo mobilizes criteria on the continuous global displacements. Walking on stilts represents an advantageous, noble position that assumes the positive side of the subject and discards Manichean terms, assuming us within a complex process of meetings and separations where we may attempt to emerge with benefit.

Amalina Bomnin

October, 2004

(1) Rolnik, Suely, Toxicómanos de identidad: Subjetividad en tiempo de globalización (Drug Addicts of Identity: Subjectivity in Times of Globalization) in Criterios No. 33, Casa de las Américas, Prince Claus Foundation for Culture and Development, p. 154.

Artworks

NDT

Alexis Leyva (Kcho) 2004Artists