Meditations

Agustín Bejarano. The Rain of the Days*

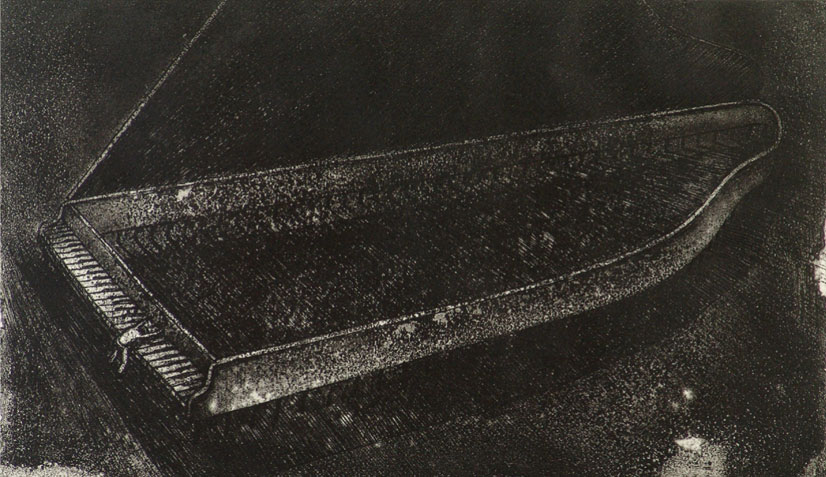

Similar to a hurricane gust was Bejarano’s entrance to the world of Cuban art. In 1987 he obtained the First Prize with the chalchographic piece Kate (1) at the National Meeting of Engraving, a show presented at the National Museum of Fine Arts of Cuba. This event – like many others from the decade of 1980 – had an important echo in the art world, the scene where multiple barriers were demolished and constant ruptures took place with regard to the stereotypes and vices of a tradition that began to be questioned and revitalized.

Bejarano, who in those days drew, painted and engraved with a strength and a fervor he still conserves, was one of the first artists in Cuba who turned engraving into an installation and three-dimensional event (2), an action registered in his series Huracanes (Hurricanes), presented at the Castle of the Royal Force in 1989 (3). Those hurricanes were an initial reflection on identity. In the center of his attention was the relationship of the human being with nature (and vice versa), and the conversion of the latter into an art object. His reflection dealt initially with the excesses of both, starting from a cardinal non-formal language, at times lyrical and sensual. The hurricane was becoming more than an atmospheric phenomenon, a symbolical expression in tune with the acceleration of contemporary life with its violence, a vital force of the individual in the face of his own struggles and a reflex of the human being that becomes a giant in the face of the tremendousness of existence. Those hurricanes of his contained the fury, the violence, the force of the whirlpools that the Caribbean as geographical zone frequently savors. Beauty, the power of movement and sensuality later prevailed next to them, in a not in the least exhibitionistic and obvious eroticism.

They wee chants to the meeting, when germinating. Forms insinuating phallic tongues, feminine pubis, vulvas, crotches, copulations that took place in the game and meeting of forms began to appear more clearly. Forms where the vegetal element predominated, which nevertheless resembles downiness; anatomies merging in indescribable form. Bejarano, in the meantime, went from the use of fabrics elaborated in mixed technique already since 1988 into monochromatic serigraphs and collographs where color had a rebirth in 1991. All of them were autonomous pieces, but connected among themselves, some of which were to become part of the exhibition Corte final presented at the Provincial Center of Plastic Arts and Design in May 1993, which ended his work up to that moment.

From 1993 through 1995 Bejarano was to develop a new theme with Brisas del alma (Breeze from the Soul). Using collagraphy he insisted in obtaining the best possible result from engraving on plastic, piercing with sewing needles which helped him to produce the details. From that moment on the formats became more moderate, with different ideas and also a morphology that enabled him to submerge more critically in the appropriation of his private and domestic space, in an evaluation of life as a couple and of the family’s daily life, in the midst of the years of Cuban life denominated special period which were deeply marked by the economic crisis and its unquestionable effects on ethics and morals in private and public life. The figuration of the series, without abandoning expression, penetrated a field characterized by a virtuous neo-expressionistic drawing that granted a somewhat unwonted leading role to the human figure as compared to his previous work.

Bejarano was self-portraying himself, and also many times in the company of his wife, who assumed the role of woman and mother at the same time. He evaluated tradition and life itself to discern with regard to the subterfuge of those multiple negotiations, collisions and conjunctions that take place at home and in the family after assuming a fragment of the individual as the entire society. His analysis included religion, misunderstandings, suffering, love, intolerance, desire and deeply-rooted male chauvinism. On the other hand, it must be acknowledged that although a good many of Bejarano’s works are influenced by his own living experiences and present an intimacy that is not exempt of drama, his vision is not distant from the collectivity. Time later he penetrated deeply into those premises, but in a tone that peculiarly marked his subsequent work. The references to domestic life were not restricted to the private space of the home and the world of his relations, but included an approach to the context as wider domain of that meaning of domestic life when searching the essence of the country, the nation and his identity.

Already in some canvases of the exhibition Tierra Fértil (Fertile Land) (4) and in his engravings on plastic from 1994 and 1995 the figure of (the Cuban) apostle began to appear as a recurrent element. His presence was not a new element in Bejarano’s work; however, those full-length figures of Martí were to become part, with unique symbolism, of the new zones where the artists interests were heading, focusing on the ups and downs of coexistence and the common environment of a couple that was becoming a nuclear family. Martí, whose head was crowned with a peasant hat, emerged within the artist’s habitat painted or drawn with a representation that oscillated between procedures somewhat close to illustration and the light but playful tone of caricature. A Martí nation in painting, he himself earth, steersman or Bejarano’s collaborator in a purifying action but as intimate as bathing time. Meanwhile, in engraving he sculpted our island in the presence of the artist and his wife, and other times, next to them, he constructed, restored, transformed, cleaned.

He turned the hero into a close, touchable being, part of the game in a new context, loaded with the contents inherent to his mythical stature and at the same time participant of the problems existing at the time the pieces were made, a period in which the economic crisis threatened to suffocate us. Wisely, the artist, after a skilful handling of irony and with a humoristic tone that could not be hidden, succeeded in avoiding the earnestness and poses in both painting and engraving, to offer us the Apostle in his quality of dear friend and support for salvation at the most critical moments. A period of overwhelming activity then arrived, in which there was a increase in the use of figures with hats, a clear reference to the man working the land, similar to those that had appeared in Tierra fértil but detached from what may be regarded as slight naturalism in the form. There also began to appear characters whose typical nature was extending in our context.

In 1995 Bejarano found himself at a point of his work that was to favor substantial transformations. There was already maturity in concepts that were to be defined since then about the representation of the city (and of society in general) as well as the conventions that would exceed their classic belonging to traditional genres such as still life, portrait, religious painting, portrait art, historical painting and landscape, in a more explicit opening regarding what is public and contextual (5).

His craft as a painter was to be enriched with the works from that period in which he still continued to contribute, with greater expression, to his work in engraving. An acknowledgment in that art form was the prize he received at the 11th Biennial of Latin American and Caribbean Engraving in San Juan, Puerto Rico, in 1995.

With Tierra húmeda (Damp Land) game between abstract gesture and a figuration presented by means of noteworthy dissolving some of the above-mentioned elements began to explode. There was a return to the earth as Magna Mater, but above all there was a return to the human being, to his origins and essences. The earth is beginning and end, but it is also the fertile one, that one, the earth of our entrails (7). The dripping, scraping and textures were not there for nothing; not even dressed in their delight in the oneiric or mythical, almost like a child who returns to his birthplace, now looking at everything with piercing eyes. This was also the moment when the artist contrasted the place he came from and the urban world in which he was now inserted.

He took interest in describing and discerning the essence of the citizen and the spirituality of the peasant, indissolubly linked to his piece of land. Precisely the latter’s spirituality discloses that El adivino (The Fortune-Teller) is a highly considered character, the same way that El Brujo (The Sorcerer) is a feared one, while the Aire del sur (Southern Air) is acknowledged and named in the cultivation of the land and the Nubes bajas (Low Clouds) are inexplicably sensed. He also left evidence of the decomposition of values considered secular and of the overwhelming spiritual impoverishment in the urban environment. In that way, a group of faces began to appear in isolated form, as prelude of the definition of multiple typologies.

Marea baja (Low Tide) reinforced and widened the contents of the previous series as to meanings and forms, articulating coherently with the theme the individual and his memory, a topic focused by the 6th Havana Biennial in 1997. Bejarano was invited to participate in this event, as part of the segment Rostros en la memoria (Recalled Faces).

This series introduced his chant to the land, praising the sense of belonging, although on the other hand it gave evidence of the exodus of the rural population toward the cities. Marea Baja consolidated and at the same time insisted on the reformulation of aspects that had only been mentioned previously, with a figuration that resisted the abandonment of abstraction but left a prodigal space to figuration. The peasant’s universe received a more lyrical treatment, and the sons of the earth became winged beings. On the other hand, elements of pop language opened a space for themselves in Bejarano’s painting. Undoubtedly, the most impacting piece of the series, which summarized the artist’s entire narration, was La isla oscura (The Dark Island). The island turned into a stage in the middle of the night. An island visited and illuminated by a spectral being that discovered the beauty crushed by darkness.

In 1997 Agustín Bejarano obtained the Grand Prix at the National Salon of Engraving with a trilogy on plastic (Harakiri, Plantas e insectos y La conquista) (Hara-Kiri, Plants and Insects, and The Conquest). His exhibition El hombre inconcluso, (exhibited at GAN Gallery, in Tokyo, in 1998, was the result of that prize. Said exhibition was significant for two essential reasons. One of them, because it brought together a wide sample of his engravings outside the country (made up by those made from 1993 through 1997, a group of works exhibited together for the first time), and the other, the international presentation of Angelotes (Chubby Children) (1998). These large format paintings were eminently in pop style, which fairly suited the artist in his interest to oppose the sense with which angels had been represented before in the history of art. His were mainly androgynous beings, some times luminous and protecting; others simulators and deceitful. Others showed off their power of aggressive hunters or their warrior strength.

In parallel to his Angelotes, Agustín Bejarano continued making engravings on plastic of the series Las coquetas (8). A refined drawing was the outstanding means that found the model in his wife. They were a contradiction with the title they bore, since the works alluded to women chased after by tradition, scourged, captive, lacerated and prisoners of a destiny predetermined and imposed on them by history and society.

In painting, there appeared in 1999 Paisaje y naturaleza muerta (Landscape and Still Life) and Anunciación (Annunciation). In Landscape… his approach was somewhat phantasmagoric. Elements of stylized crockery which recalled those used by the Cuban 19th century bourgeoisie, brought from Europe shined from inside and also contained other views on their inner part: miniatures of other locations, furniture and architectonic reference and even portraits. An old-looking atmosphere due to the passing of time loomed over these works that revived in an organic though unusual way the theme of the classic still lives.

In the Anunciaciones (Annunciations) (9), although he broached a biblical theme, Agustín Bejarano’s game pointed in another direction. The Middle Ages and in like manner the Renaissance spirit were evoked without reaching the quotation or the appropriation. Each work was a fragment in which the narrated event was displaced to a different dimension. The religious incarnation transcended to leave the matter in question open to other creeds and particularly to the worldly kingdom. Thus, the theme was transported to a contemporariness that added advertisement, tattoos and graffiti. His icons were to have a contextual familiarity in ambiguous and sensual characters, submerged in luminous nights and among animated vegetal networks that wrapped, tied, intertwined and also repressed. The whispered, sung and danced signals in Anunciación were focused on a theatrical territory inhabited by a hybridization of ideas and resources at the service of a different way of broaching and manipulating the theme, to stop then in the human element, in the voluptuousness of the bodies, underlined by the chiaroscuro and the recreation of shades in the volumes. Bejarano raised his voice in a praise of fertility, but above all he praised the enigma. He wanted to register particularly the fleeting instant of revelation in its magic. Bejarano has been evidently an artist who has rejected the unity of styles with a lively interest in renewing themes profusely broached in the history of art, the way it also happened with the portrait of his series Cabezas mágicas. The portrayed characters integrated with their austere environments, and although at times they were represented up to the waist and even full-length, conceptually, from the very title of the series, the symbolical reference concerning the heads was focusing on those elements that generate ideas, on the force and powers of the mind, pondering it as receptacle of the spiritual, in analogy with Plato’s idea that the human head is the image of the world.

The series praised the epic of daily life. A daily life whose simplicity and fleeting nature build the epic of the common man. Here there was space for farewells, expectancies, wounds and also for savagery, shipwrecks and metamorphoses. The artist thus disentangled the scheme of events and, at the same time, of the individual memory, to deliver a sketch of his own experience through many of the figures alienated from the great discourse of history.

Cabezas mágicas (Magic Heads), presented at the Havana Club Foundation in Havana, was a kind of resurrection of the portrait theme. Portraits lost in thought of the represented, invoked types. Generic abstractions (Tejedora de mano, Pescador, Retrato de muchacha) (Weaver, Fisherman, Portrait of a Girl) (10), which presented fictional faces recreating the anonymous and, in unison, multiple figureheads of the streets.

In 2001, the piece Imágenes en el tiempo III (Images in Time III) (11) was included in the exhibition La Belleza y la fuerza (Beauty and Force) presented in New York by The Elkon Gallery. That canvas belonged to the series of equal name started by Bejarano in 1997 and taken again the same year of the New York show. Martí was emerging again in Agustín Bejaranos art work with unstoppable force, assumed from a posture that differed from what had previously been made in painting and engraving. If initially his allusions to the Apostle had stopped in his imagery, in the political figure he was and in the citizen with whom the artist had shared his intimacy, at this point it was the hero who was being reborn from a glance that praised the sacred and epic through the exaltation of his exceptional spirituality. The metaphor gained greater tropologic height when broaching the mythic stature of the man who has given his own myth more than enough reasons of existence.

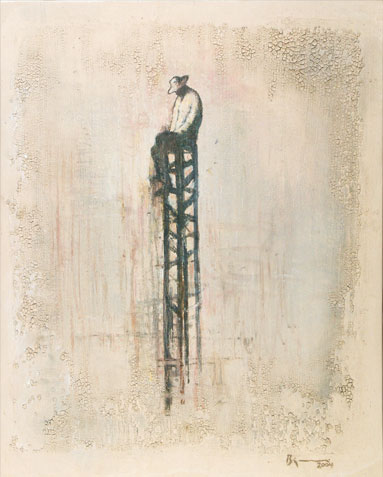

All that Bejarano had made as an artist up to that moment was consciously filtered until turning it into legacy within this series. The plastic resources allowed perceiving at some moments the draftsman, but the greater echo was produced by the painter in the modeling of his figuration. The intentional recurrence to the siennas, ochres and sepias; the game he played with their intensity, not only on backgrounds but on the entire canvas surfaces, together with the crackeling and glazing, underlined the textures, and had the purpose, on one side, of reinforcing the passing of time, and on the other, of exacerbating the force of the earth-human race link. The symbolical value contributed to the former by other elements sought to unite the human race to everything it is, has been and will be, and not to the fashion of one day (12).

In his series, Bejarano established a critical distance from the conventions of heroic portraits. The figures of Martí in his works did not belong in pedestals. He avoided the solemnity to take pleasure in the affection toward the Martí that history hardens and distances from the common individual. The artist animated in these portraits, a painting that reflected on an idea, a sensibility, an ethics: that of a unique (not perfect), paradigmatic man, dedicated to cultivate sacrifice, justice, love and tenderness. Devoted to the liberation of his country, attentive at the same time to the fate of America, with a group of ideas valid for all humankind. A man who always rose above his loneliness, his anguish and the physical fragility of his body. With Imágenes en el tiempo, Bejarano succeeded in presenting to us the humanistic profile of that Martí who transcends the local reference and extends in universal scope.

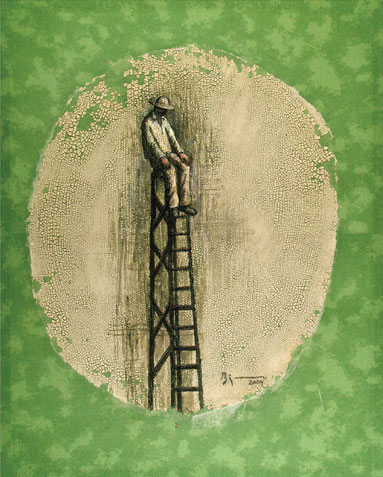

Imágenes… was exempt of the usual demands in the representation of historical personalities. The physical resemblance was not cardinal but indeed the essence of the character was. His body was many times fragmented when required by the symbolism. The immanence of his visionary, illuminating ideas and the grandeur of his actions was underlined. Martí appeared many times as a winged being, equivalent to messenger, guide, with the vigor of a hummingbird sustained in the current of time. For that reason, his figure also appeared on scaffolds and ladders, halfway between dreams and the harshness of reality, between the utopias and the journey to concretize them. There it was: his big hand, instrument of the maker, of the giver. His body, the earth. His body, the fountain.

It was committed with the spirituality that flowed from Imágenes en el tiempo and from itself, intertwined during a period in which a definite separation was still difficult and hasty, that Agustín Bejarano’s most recent series, Los ritos del silencio, was defined.

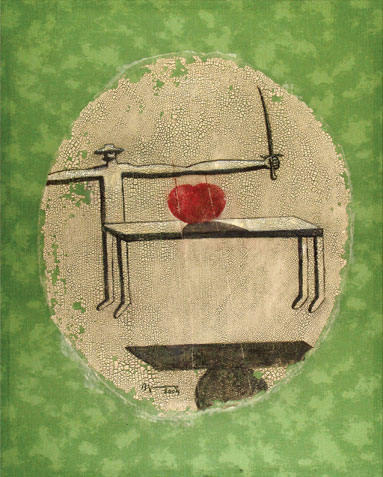

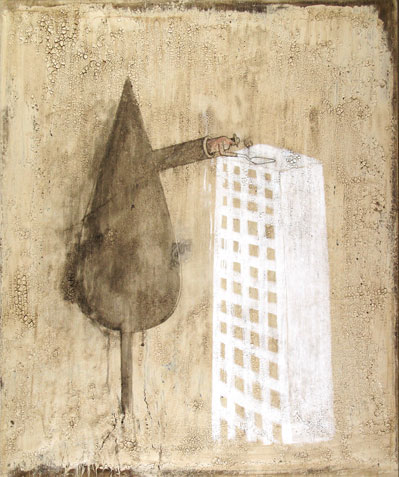

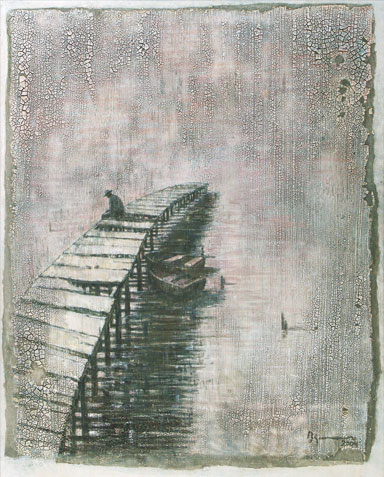

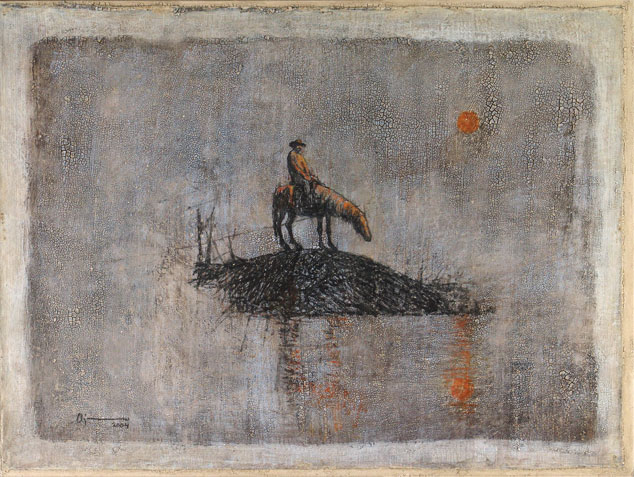

In Los ritos… there is a man, undoubtedly portrayed, but in the way in which Bejarano assumes this event. His portraits deconstruct the genre and at the same time the subject of the representation. Following a generic abstraction, the man emerges with no differences. Each piece about him is a metaphor of longings, needs, anguish, loneliness, dreams and desires. Bejarano denounces these scourges, leaves evidence of their perpetuity, while he dissects the spirit of the present from its very medulla. Aridness fills up what could be benevolent landscapes, and they are places of vociferous sterility. Large, medium and small formats have been used by Bejarano in these ceremonies related with silence. The representations refer to small beings (upon whom the entire weight of humankind seems to fall), wearing hats and frequently carrying huge wings, placed at the top of scaffolds and ladders to additionally establish an intimate relation with the desolate and austere landscapes of philosophical background close to Zen where the existence of craters and abysses, city shadows and phantasmagoric villages with squalid trees has become a routine.

Not in the least classic are the locations he takes us to with the skill of a surgeon when he makes a deep cut to show us some of the groups of problems that suffocate contemporary society: lack of communication, loneliness and the fragility and impotence of the individual of our days in the face of the huge conflicts pending upon him.

The painting resources create a supernatural and desolated atmosphere in which his characters calm down their spirit, absorbed by an omnipotent superior force inhabiting them. A force that some were to call in equivocal way the submission to fate, but which is simply the reflection of the challenge of existing expressed in the dispute taking place between silence and void.

There is a special meaning in the election of humble, ordinary human beings in the midst of their sufferings with the tremendous effect of the absent voice; strength to protect the true pain of their simulacrum and of the weakness there sometimes exists in admitting it. These men of simple appearance, not by chance placed by Bejarano in his landscapes, are the stressing vision of the human drama, of the struggle for dreams, hope, passion; for each fragment of life itself that is debated between the limits imposed by the circumstances.

These rites are a trial of strength, and their leading figures have a sacred stature that demands no mercy; they are a sign of depression but under no circumstances of defeat. That is why he chose men that were not touched by frivolity, pure in their very essence and in that of their work (fishermen, peasants or utopians); men who carry their truth with them and even if profane search pity in inner enlightenment, in meditation, be it by letting time go by in broken-down piers or rustic scaffolds, or in the unforeseeable water current, in the sea, the river or in dreams. The silence that accompanies them annuls the weeping, rage, sadness, fury, frustration, hatred, and keeps the roar inside until silencing it and finding the right path for their crossroads. That is why the majority of the paintings are ordered from a center; chaos has no place in these landscapes, in these meditations of men who remain silent but search while they surrender or abandon themselves temporarily to nature. Landscapes are the place of communion of people who seek to wake up, abandon all doubt about themselves, resist the most crucial tensions to find the illumination of the own conscience. Here are undoubtedly their intimate adventures, their journeys. Inside each chest is a sustained prayer, that is why I distinguish the actors of Los ritos del silencio as persons at prayer allow me to call them that who worship silence, but are nevertheless anxious of obtaining answers.

In the infinity of a nature that is more symbolical than naturalistic and in addition extensive, plentiful in its luminous effects or in the densities of its darkness, men and places converge. The act of silence is the rite, and the universe its landscape. Their copulation makes everything flood, annulling the void, and the mind of those who remain silent becomes a window between outside and inside. Precisely at that moment that inner beast we all have been possessed by at one time is destroyed.

Los ritos del silencio (13) were the moment of greatest synthesis in his work. His painting action in them turns limpid, austere, and has become a space in which, with sharpness and coherence, the entire recurrence to a memory of anthropological nature is displayed where the leading characters are peripheral individuals, inhabitants of ghettos almost in extinction, a hardly whispering otherness.

Penetrating the scheme of Agustín Bejaranos art work presupposes not taking hastily into consideration his multiple transits, not trying to separate series or stages, because in the creation of his discourse there is no abrupt violence but a peculiar metamorphosis and a constant mixing that takes him from one place to the other with a conceptual and morphological coherence that is marked by the patrimony of his own exercise.

To be able to discern correctly the discourse he has constructed it is necessary to leave out any stereotyped vision, only referred to that part of his work comprising the constant formal mobility and change in its most superficial value. To grasp his work means penetrating him beyond the permanent experiment and the decontamination of stereotypes. That makes it possible to distinguish how in the substrate of his work, in its framework, and also on the surface itself, there is a continuum whose meaning lies in the mortar of history in a self-referential perspective, in a journey from private (or intimate) to social, and to the context of the primitive.

The living experiences and daily life are nourishing substances of his works. His way of assuming them has gradually endowed his symbolical production with the capacity of transcending the time and space in which they were created, even if they were born inside a particular social and human nature.

The artist has succeeded in carrying on, in the midst of very diverse proposals, an aesthetic ideology without fissures, in his search of what is rooted in the group. He has made us perceive again Martí’s sense of the earth as world, of the earth as humankind. Figurative and abstract, or semi abstract, have been formal resources that sustain his idea of the contradiction between progress and tradition and the marks they leave in society.

Bejarano’s work does not escape the influence of today’s convulsing society and its multiple juxtapositions as to times and memories of very diverse natures. He has chosen not to be an accomplice of a contemporary world where true spirituality is scarce and attempts to bring out of anonymity the modern man’s existential crisis and his helplessness.

This man that Bejarano has decided to show in his abandonment has passed along and excelled his own limits through prayer, pleading and meditation while silence is repeated as echo. Something intense and unmentionable arrives, falls, invades with its density the place reserved for that voice in despair that would like to be heard. Here are revelations whisked away by silence. There may be an intense rainfall, but time is something else. Fine drizzle in the course of time. Time, an unruffled drizzle. The weight goes inside the man’s chest, suffocating him; nothing breaks it, nothing frees him, a hat is his only protection. A man yesterday, now, always, under the eternal days’ rain.

Caridad Blanco de la Cruz

Quotations and notes

* This article is a reduced version of a longer text with the same title, still unpublished.

(1) That chalcograph alluded to a hurricane of the same name that scourged Cuba in 1987.

(2) The sculptural installation Vida (Life), 1989. Chalcograph and acetate. 200 x 500 cm, made with chalcographs and acetates, is the most outstanding example in that regard.

(3) In 1989 he graduated from the specialty of Engraving at the Higher Institute of Art in Havana, and inaugurated in his home town the Taller de Grabado de Camagüey (engraving workshop of Camagüey), where he was director two years.

(4) The title of this exhibition refers to one of the pieces included in it at Galería Habana in 1994. Tierra fértil (Fertile Land), 1993, oil/canvas, 130×151 cm, was José Martí’s body turned into an island.

(5) This period corresponds to his series Voluntad de Silencio from 1996, year that the artist spent in Monterrey. With the same title, part of it, together with a considerable number of the engravings from the series Brisas del alma (Soul Breeze), was presented at Nina Menocal gallery, in Mexico, that same year.

(6) Series he created in 1996 and 1997. Part of it was exhibited for the first time at the Development Center for the Visual Arts in Havana, Cuba, in August 1996, and later at Lausín

Artworks

The Rites of Silence CXXXIX

Agustín Bejarano 2004The Rites of Silence III

Agustín Bejarano 2004The rites of silence CXXIV

Agustín Bejarano 2004The Rites of Silence CXXXVIII

Agustín Bejarano 2004The Rites of Silence CXXV

Agustín Bejarano 2004The Rites of Silence CXXVI

Agustín Bejarano 2004The Rites of Silence CXL

Agustín Bejarano 2004The Rites of Silence LXXVII

Agustín Bejarano 2004The Rites of Silence CL

Agustín Bejarano 2004The Rites of Silence CXLI

Agustín Bejarano 2004The Rites of Silence CXLII

Agustín Bejarano 2004The Rites of Silence CXLIII

Agustín Bejarano 2004The Rites of Silence CXLIV

Agustín Bejarano 2004The Rites of Silence II

Agustín Bejarano 2004The Rites of Silence CXV

Agustín Bejarano 2004The Rites of Silence IL

Agustín Bejarano 2004The Rites of Silence CXLIII

Agustín Bejarano 2004Artists