Saltpeter

The Gold of Having Nothing

The grandmother firmly holds the oil lamp, about to fall, while her arms get sores. The scar was to last a lifetime. Two brothers cross day after day, in the morning and in the afternoon, when returning, the viscose mangrove tree path in order to go to school, which was five kilometers away from the house. A boy walks along the shore, as if playing a solitary game, until that sublime hour when the sun stands right in the middle of the sky dome. His toys are the waves, the sea conchs, the hot south breeze, the crabs he finds on his way, broken glass where the sun refracts the light in small, brilliant rainbows. Days of blue dawns and brilliant sunsets that end with the sky full of stars. His glance nails itself to the sky with each change of home and of landscape, without knowing that he wished the universe. The sea chases him as much as the memory of his grandmother, and that permanent sensation of finding an absolute. The grandmother, who left him for eternity a comb and an eraser when she died, perhaps to tell him without words that sometimes, in order to advance, you have to erase that minute that remained behind and we do not forget. Time that goes by and poverty that does not stop. The mother who struggles without being able to say enough, and the noise of the hand tool, and the screams of the foster father while his breath smells of beaten lovers. Poverty of the soul that tires, ages, while friends go by, few remain and many go behind that sour/sweet limit of the Island that blows you up with its infinite extension. The family dissolves in an unintelligible present where father and sister are on the other side; parallel dimensions for oblivion and memory.

With the eyes fixed on the horizon line, many times mental, you learn about that involuntary clock of time and death, and of the nomadic loves born by chance, of the involuntary whim where you perceive the preconceived future of your will: that woman will be mine. And one day you climbed the aluminum tube that shortens spaces and time. You saw that yours is the problem of everything, of everyone. Control, power, dogma, censure, marginality and money. The dammed money that Shakespeare called go-between of History, although on his last day he won the title of coarse pawnbroker. Owo, owo is always driving, says Orula. Owo to live and help others, but the touch of Midas is a curse that, instead of bringing together, separates friends, families, husbands from wives, brothers from brothers, fathers from sons. Owo, and it is never enough for anyone.

Another time, another space: the mad adolescent who gives flowers as presents, ends, after a while, asking for help. The aged woman who does not have a place to live in and stops you on the sidewalks, in parks, disheveled and dirty, begging. The children who run in the streets of Old Havana, shaking the pockets of foreigners. The young couple that has no place where to make love, cuddle in the corners, in the dark benches of lost parks. The drunkard of sleepy eyes who does not know where to find money to sink his miseries in a bottle. The prostitute that underlines her charms, smiles and opens her eyes, sweetens words and gestures for someone, ignoring how he will treat her, while her pimp watches over her. People count their money day after day, cent by cent, so that the salary will last until the next payday. Greed of scarcity that testifies an oracle of prevision. Deceived and deceivers, victims and victimizers, all rogues who are part of the same vicious circle where no one knows who is who. Is it possible that there is nothing stronger than the wish of comfort, of status, of power, of public image? Minimalism of survival as thickness of an existence that has become struggle. Metaphor of the coin that never succeeds in calming down the thirst of the thirsty. The economy of a country debates itself between two currencies. A CUC is worth twenty-three Cuban pesos, and almost nothing costs less than one Cuban peso, while everything crashes against the infinite mathematics that suggests an economic and social reality that turns round the CUC. CUC, acronym indicating its position of freely convertible currency, or, what is the same, its capacity to be changed against other international currencies. Money, value of use, value of change. Everything has a price; safe paraphrase of something revealing; they all have a price. Merchandise of the object and the subject, who has become an object. Daily exegesis where, unfortunately, many times material poverty validates a poverty of the spirit. Hard reality that perverts the most unharmed gesture to grab the destination of the money-merchandise-money or of the merchandise-money-merchandise. Karl Marx did not brandish arms against the divisions of a social system, he planned to reshape the essences of humankind.

The Island, now in free convertible pesos and, of course, the fixed, damned circumstance of water everywhere. And it is the disorder of the Tropics, so many times blessed and condemned, because already long ago it was said that the Kings laws in the continent were one thing and another thing those same laws in the island colonies. Anyway, names inevitably accompany mens fantasies. Cuba, that resisted in preserving its original name, means insular, worked land or Paradise in Aruaco. Cuba, the space where it is possible to try to achieve the dream of the impossible. Saltpeter: saline substance, known in chemistry as nitro or potassium nitrate, which emerges in lands and walls near the sea. Boiled egg with water and salt instead of sugar water. Empthy, and the fridge awoken from its winter dream by twelve-hour blackouts and thermal steams of 38º in the dark July and August nights in the early nineties. Beefsteaks made of grapefruit shell and ground green banana shell instead of ground meat. Men and women thin almost up to anorexia, pedaling Chinese bikes to reach some point of a city that fell apart from the inertia of its inhabitants. Silence, and at times the hollow sound of a Chinese cornet playing the National Anthem at a distance. Silence, and skepticism sweeping away the best of our soul. How to recompose the fragments of that long and somber night that still remains for many? It is not enough to resist; it is not enough to fight. The feeling of far away is so strong that the evasion, both physical and spiritual, invades everything. Young people speak of individual micro utopias and old people speak of crisis, a crisis that persists in being almost a lifetime, over fifteen years.

Undertow

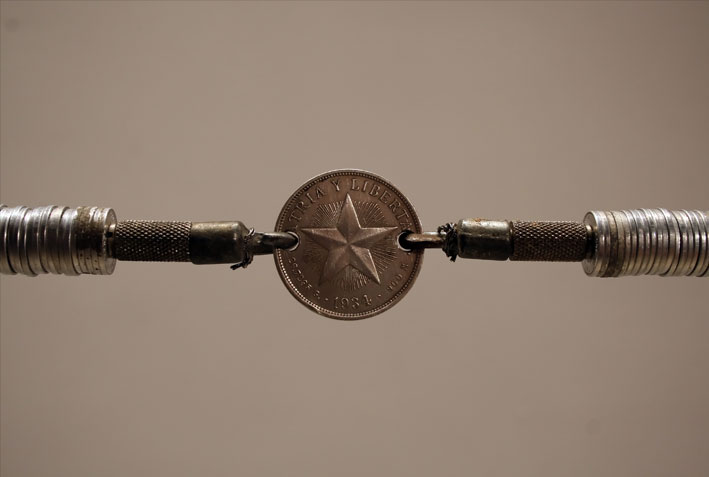

Saltpeter is a non-cheated crime. Everything is here by a kind of pervert cynicism highlighted by art’s dual and inalienable condition of merchandise and object of aesthetic meaning. In it we find the diatribe of one who perceives intuitively the gradual and systematic destruction of a national essence, effective in ways of acting, of thinking, and in material values, their value of use and of exchange. In short, the history of a nation for the history of its economic capital. Saltpeter is a punch in the face, considering the economic restriction implied in the fact that it was totally financed with national currency. The ineffectiveness of this type of currency points to the crack of a historical process as metaphorical transposition, where the heroes, mottos and emblems of the Fatherland that appear as images in the currency are devaluated in political, historical, social and moral terms when said currency is economically devaluated. At the same time, in its presentation as an art work, the national currency gains legitimacy, not because of its value of use, but for the value of exchange granted by this condition. Money thus changes into art merchandise, both tangible and intangible, and as such changeable and saleable under these new terms. The end result is forms that, at first glance seem unexpectedly naïve when the truth is that they contain a glossary of intentions. Details like the height of the mythical or real history of the hero to which they allude are subliminal messages activated by the title of each piece. Once more art and market, art and society, utopia and pragmatism go together in the uninterrupted marasmus of sketching ideologies.

It is possible to establish relations between Saltpeter and the radiant concept of poverty articulated by José Lezama Lima to discourse on José Martí, the fathers of the nation and the Cuban Revolution. And I quote: “The wakefulness, the sharpness, the affliction of the poor man drive him to an infinite possibility (…) the impossible, when acting on the possible, conceives a potens, which is the possible in the infiniteness.” National currency, and with it the preeminence of a style of poverty and its infinite possibilities in the ordinary Cuban. As if unwilling to, Saltpeter hints to the problem of the Cuban-ness from the resistance of a people that exists beyond the flat notions of a patriotism that bites its tail. This willingness re-conducts stereotypes of the Cuban, at least that univocal glance that links it to political-ideological considerations, to grasp a (self) conscience of the national history. Saltpeter restores to us a possibility where the Cuban may think of himself as he is: as he wants to be, as he should be and as he can be.

Sandra Sosa Fernández

Artworks

Professional tripod (detail)

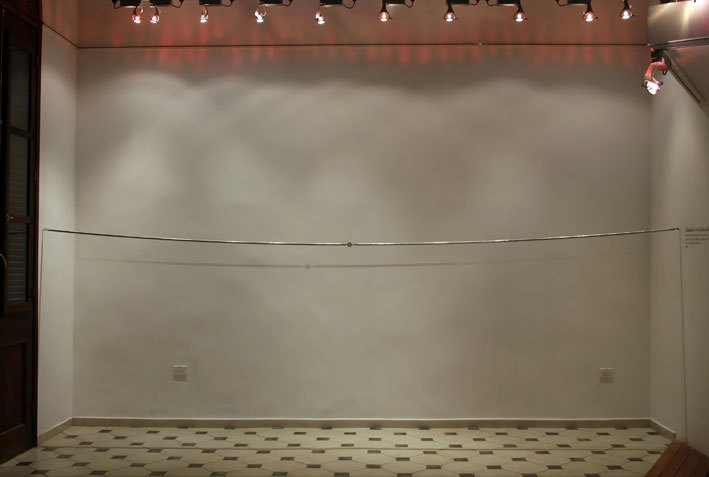

Eduardo Ponjuán 2007Professional tripod

Eduardo Ponjuán 2007Professional tripod (detail)

Eduardo Ponjuán 2007Harpoon

Eduardo Ponjuán 2007Lightning Rod

Eduardo Ponjuán 2007Lightning Rod (detail)

Eduardo Ponjuán 2007Sunk in the Horizon Line

Eduardo Ponjuán 2007Sunk in the Horizon Line (detail)

Eduardo Ponjuán 2007Artists