Angelus

Angelus or the pictorial reincarnation of cuban reality

Agustín Villafaña, versatile Cuban visual artist, inaugurated the show Angelus in Villa Manuela Gallery, of the Association of Writers and Artists of Cuba (UNEAC). The exhibited works are part of other recent series, among them Antonia, which recalls the aesthetics of Antonia Eiriz, outstanding Cuban painter of the sixties; Angels of Havana and Shadows.

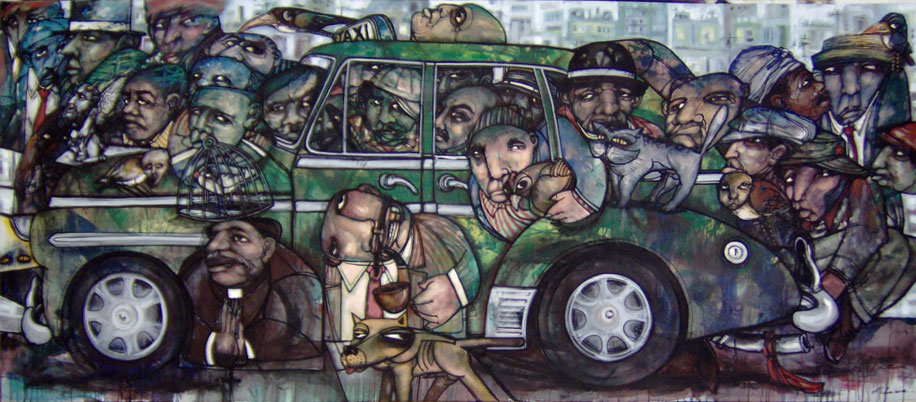

The pieces are a representation of the searches carried out by the author of the peculiarities of his environment and of the human beings who inhabit it. Daily life in his country is transferred to a visual language with peculiar tints of expressionism, with an outstanding taste for the reflection of the subjectivity and inner feelings based on the deformed and the ugly, characteristics that, endorsed by their reiteration along the years, make up Villafaña’s distinctive language.

The combination of forms, beings and colors in his proposals does not attempt to be pleasant or obliging; on the contrary, it demands the viewers’ concern and commotion when they recognize themselves in each piece as part of a history that is re-written with every passing day.

The paintings from the series Angels of Havana bring together characters that are popularly recognized in the capital because of the social function they perform. The individual anonymity ceases to exist when the peanut vendor and the coffee vendor in every corner are identified, but also Ángel Aguiar, handicapped by blindness, who claims for company to cross the streets and go on selling light merchandise, or Ángel Santo, who strolls about in the city carrying a small statue of a saint in his hands.

The force of Villafaña’s elaboration lies in the faces, where the eyes and glance become themes underlying his works. Kidnapping of the Old American Car, Inhabitable Space and Last One, Please, are three large canvases showing group actions in which the ethnic and social variety of Cubans are represented. They show the duality of good and evil, true and false and real and invented that is inherent to everything that surrounds us. On this subject, the artist explains: The element eye creates an internal rhythm in the pieces; the study of faces and the expression of the glance help me show the angelical and infernal existing in each person. After a moment of silence facing the works he finally says: Because Paradise may be infernal, and what is pleasurable may also be in hell.

This time Agustín does not return to the gallery as the ceramist who loves technical experimentation, but as the author who expresses what he feels with the help of acrylic, inks, fabrics, dirty paper and cardboard. In the absence of the discipline that has earned him multiple acknowledgments in his work, he comments: Although this curatorial proposal does not include ceramic pieces, that does not mean I abandoned it. Before being a ceramist I learned to draw and to print, that is why I don’t like being pigeonholed. Ceramics is more docile and fertile to express what I want, that is why I will not stop making it, nor will I forget the remaining forms. I use indistinctly any one of them that helps me express myself.

Regarding future work with that technique he advanced: With ceramics I have in mind a creative opening that includes new art concepts with appropriations of dissimilar objects thrown away by the human beings.

Villafaña, a creator with more than 27 years of experience in the teaching of the arts, proud to contribute to the education of several contemporary Cuban artists like Alexis Leyva (Kacho), Javier Guerra and Reinerio Tamayo, just to mention some, acknowledges and pays tribute with the exhibition to those teachers and artists who have been participating in the teaching of art since it started in the Island.

Like any other restless and hardworking creator, always with new ideas, he commented on his current activities: I am now interested in fostering the creativity of children and adults over 60 years of age. Through the Yeti Art Community Project I organize the amateurs in the neighborhood of La Ceiba, municipality of Playa, and approach to creation those who think they do not know how. I give them tools and teach them the procedures of painting, ceramics and engraving, so that they may express themselves. It is a community project to promote the qualification not just of the art instructors but of the people in the neighborhood.

By Yanelis Abreu

Artworks

From the series Angelus: The Last One, Please

Agustín A. Villafaña Rodríguez 2007From the series Angelus: Kidnapping of the Old American Car

Agustín A. Villafaña Rodríguez 2007From the series Angelus: Inhabitable Space

Agustín A. Villafaña Rodríguez 2007Block Sketches for Outline

Agustín A. Villafaña Rodríguez 2006Block Sketches for Outline

Agustín A. Villafaña Rodríguez 2006Block Sketches for Outline

Agustín A. Villafaña Rodríguez 2006Block Sketches for Outline

Agustín A. Villafaña Rodríguez 2006From the series Shadow

Agustín A. Villafaña Rodríguez 2004From the series Shadow

Agustín A. Villafaña Rodríguez 2004Artists